Twenty years ago, on April 20th, 1999, 12 students and 1 teacher were killed and 21 people were injured in a horrific shooting at Columbine High School. On that day I didn’t know how this would affect our industry and my career. Twenty years ago it was impossible to imagine that school shootings would become common enough to support consultants and training programs designed to secure schools and prepare for a shooting. Who knew that we would need a standard – NFPA 3000 – to help facilities prepare for, respond to, and recover from an active shooter / hostile event? Dozens – even hundreds of products have been introduced, from barricade devices to bullet-resistant backpacks. States have created task forces, new laws have been proposed, and each school shooting has been studied at length, in hopes of avoiding another one, or at least limiting the casualties.

Twenty years ago, on April 20th, 1999, 12 students and 1 teacher were killed and 21 people were injured in a horrific shooting at Columbine High School. On that day I didn’t know how this would affect our industry and my career. Twenty years ago it was impossible to imagine that school shootings would become common enough to support consultants and training programs designed to secure schools and prepare for a shooting. Who knew that we would need a standard – NFPA 3000 – to help facilities prepare for, respond to, and recover from an active shooter / hostile event? Dozens – even hundreds of products have been introduced, from barricade devices to bullet-resistant backpacks. States have created task forces, new laws have been proposed, and each school shooting has been studied at length, in hopes of avoiding another one, or at least limiting the casualties.

In the past few weeks there have been dozens of articles about Columbine and school security in general. How has the Columbine shooting affected school security? What improvements have been made in the last 20 years? Are any of these efforts working? Are the investments money well spent? How are these changes affecting students and teachers? Are today’s schools safe?

Three articles stood out to me – two from the Washington Post and one from the Globe Post. The Globe Post article is titled: No, We Are Not Facing a Crisis in School Safety, and draws on two decades of data and various reports and studies to make the case that schools are safe:

Taken as a whole, the evidence suggests schools are generally safe and that we are not experiencing a general trend towards more school violence. While any loss of life at school is tragic and unnecessary, our responses should be grounded in the evidence rather than false narratives about increasingly unsafe schools.

Increases in school security measures over the last several decades may be responding to a false perception of a problem. Worryingly, these responses, like more police in schools, harsher discipline, and other security measures, can actually have negative unintended consequences. Some argue then that the “real school safety problem” is not violence but the overly harsh response by schools.

One of the Washington Post articles, Study: There’s no evidence that hardening schools to make kids safer from gun violence actually works, is based on a recent study conducted by researchers at the University of Toledo and Ball State University:

Schools use a variety of practices to make campuses more resistant to attacks, including employing armed school resource officers; installing video cameras, bulletproof glass and metal detectors; requiring teachers and staff to wear identification tags; establishing schoolwide electronic notification systems; limiting open access to a school; developing active shooter plans; and conducting neighborhood police patrols.

The researchers concluded that the “ideal method for eliminating school firearm violence by youths is to prevent them from ever gaining access to firearms,” but, “unfortunately, studies have found an alarming rate of firearms accessible to youths.”

A second approach is assuming young people can obtain weapons but installing measures that will prevent guns from entering schools, the report says.

The third article, The man keeping Columbine safe, is a detailed look into the current challenges faced by the schools in Jefferson County, Colorado. Many of these concerns are likely shared by other school districts across the country. The article follows John McDonald, who is responsible for the security of the schools in the Jeffco district, including Columbine High School. When the article describes the current state of one of the schools, I know that many of you will spot the same thing that drew my attention:

They also didn’t have a blueprint of Columbine when they arrived, meaning many had no sense of the layout inside. Now McDonald keeps detailed floor plans of all 157 schools in his trunk, along with extra ammunition, a bulletproof vest, a sledgehammer and an emergency stash of Peanut M&Ms for his diabetes.

He stepped out of his car and appeared on one of the school’s dozens of security cameras. More were being installed before the anniversary. He entered through a door his dispatchers have the capability to lock or unlock. Each classroom he passed was equipped with a deadbolt that locks from the inside with a simple turn. No more teachers stuck in the hallway, fumbling with a ring of keys.

Each classroom was equipped with a deadbolt? Based on what I know about the security in the district, I believe this refers to mortise locks with integral deadbolts rather than separate deadbolts which would not be compliant with Colorado’s building code or fire code.

I agree that based on the data, the odds of a school shooting occurring in a given school are extremely low, and I don’t encourage school districts to invest in unnecessary security. In my opinion, it’s important for schools to have, at minimum, exterior doors that prevent unauthorized access to the building, and classroom doors that can be locked by teachers. A secure vestibule at the main entrance, monitored perimeter exits, and lockable doors to compartmentalize the building can increase the layers of security and the safety of the building occupants – not just during a shooting but during normal operation of the school. And as always, when considering added security, it’s critical to comply with the adopted building codes and fire codes, to ensure that students and teachers have the ability to evacuate freely.

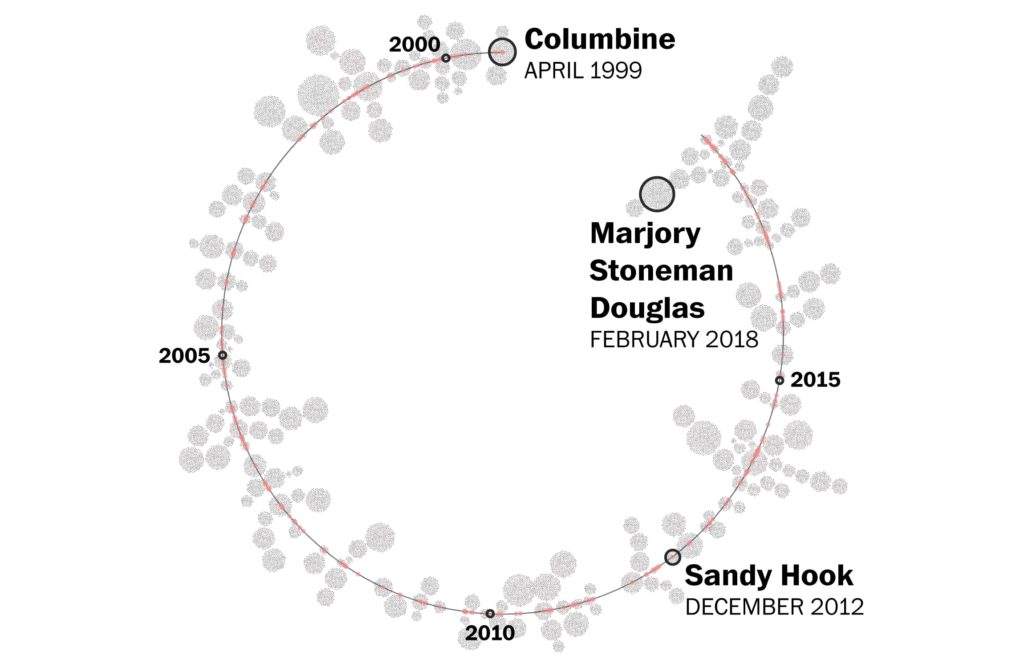

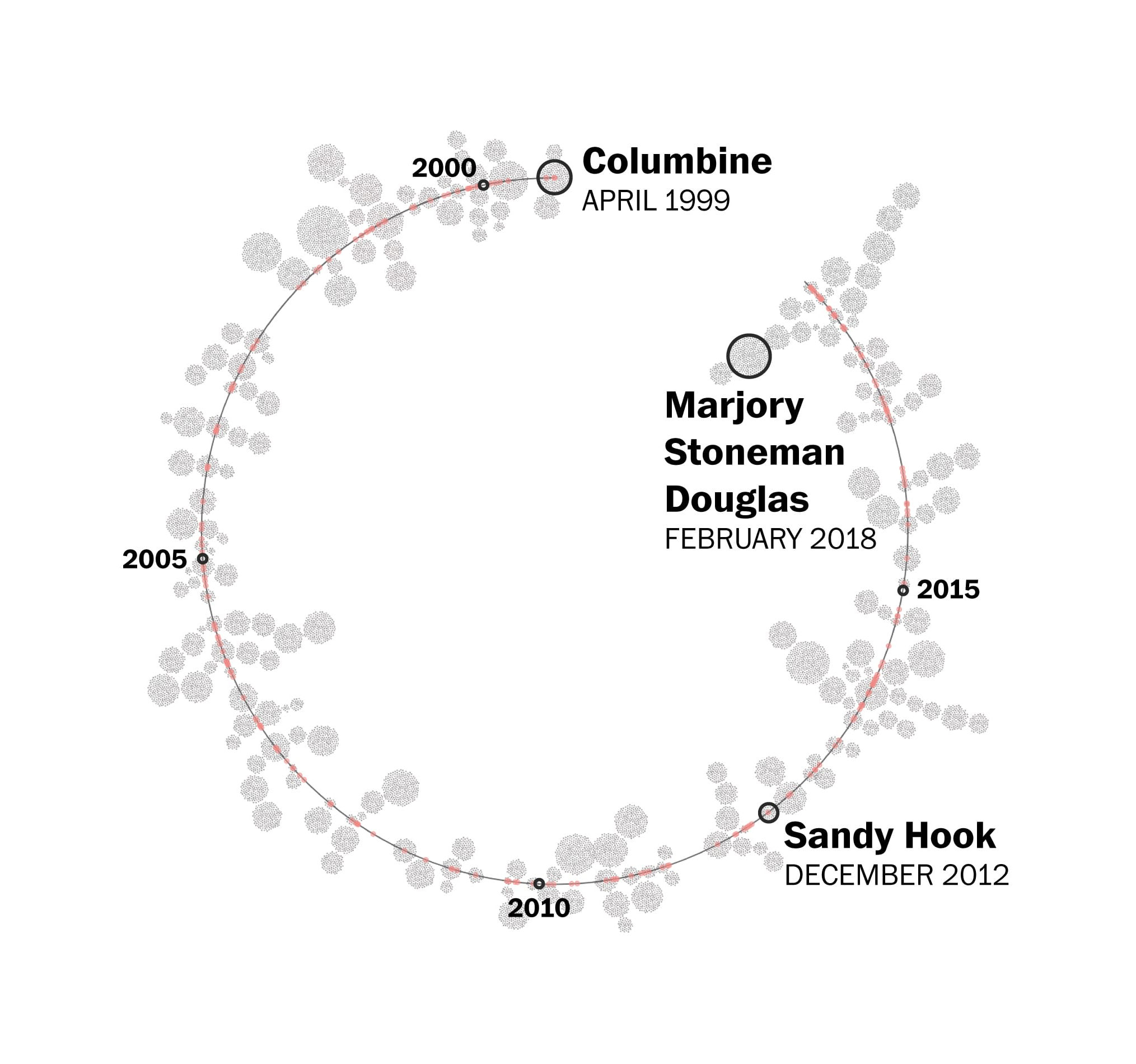

Graphic: Washington Post

You need to login or register to bookmark/favorite this content.

Leave A Comment