I’ve edited this article and the downloadable PDF…feel free to share it!

This post was published in the May 2015 issue of Doors & Hardware

[Click here to download the reprint of this article.]

There is a question currently under debate in several jurisdictions across the country – should barricade devices be used to secure classroom doors during an active-shooter incident? These devices have emerged in the last few years in response to fears that inadequate security may leave classrooms vulnerable. The devices are typically designed to be installed on classroom doors during a lockdown, in addition to the existing hardware. While barricading the door with a device of this type may seem to address the immediate need for security, one should consider the safety concerns associated with this practice.

There is a question currently under debate in several jurisdictions across the country – should barricade devices be used to secure classroom doors during an active-shooter incident? These devices have emerged in the last few years in response to fears that inadequate security may leave classrooms vulnerable. The devices are typically designed to be installed on classroom doors during a lockdown, in addition to the existing hardware. While barricading the door with a device of this type may seem to address the immediate need for security, one should consider the safety concerns associated with this practice.

Conventional locksets meet the code requirements for free egress – allowing occupants to exit without obstruction, fire protection – compartmentalizing the building to deter the spread of smoke and flames, and accessibility – ensuring access for all, including people with disabilities. These locksets will effectively secure classrooms against active shooters; in fact, testimony presented to the Sandy Hook Advisory Commission indicated that an active shooter has never breached a locked classroom door by defeating the lock.

By definition, the word barricade means “to block (something) so that people or things cannot enter or leave” (Merriam-Webster.com). Most codes require doors in a means of egress to provide free egress at all times, which allows building occupants to evacuate quickly if necessary. Some proponents of barricade devices suggest that because the device is intended for use only when an active shooter is in the building, securing the door takes priority over allowing safe evacuation. Those on the other side of the debate believe that because there is no guarantee the device will only be installed under these limited circumstances, the devices could be misused, preventing authorized access by staff and emergency responders, as well as delaying or preventing egress.

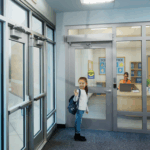

Exit doors in a school, chained to provide security. This locking method does not meet IBC, IFC, or NFPA 101 requirements for free egress. Photo: Wayne Ficklin, Architect

Some advocates of these locking methods have stated that if the product is not permanently attached to the door, it is not under the jurisdiction of the code official and is not subject to the same requirements that door locks and security hardware must comply with. Following this premise, panic hardware secured with padlocks and chains would not be under the code officials’ jurisdiction either. In reality, code officials address these unsafe temporary locking methods frequently, as most codes do not differentiate between a device used temporarily, and a permanently-installed device. Fire doors blocked open with wood wedges or other creative (but “temporary”) hold-open devices create an obvious fire protection problem, and again, the code official is responsible for enforcing the code requirements even though the offending devices are not permanently attached.

Comparisons have been drawn between the use of furniture as a barricade, and the installation of a barricade device. Barricading a location with furniture and other environmental items is a secondary response for incidents of active shooter and terrorism and is recommended if evacuation as a primary response is not possible. Such barricading is recommended by many organizations, including the ALICE Training Institute, the US Department of Homeland Security, the Department of Education, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the Department of Justice, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). However, none of these recommendations involve the installation of secondary door locking devices. Barricading uses gross motor skills, is applicable in any location, and does not require a door or special door locking device.

The ALICE Training Institute recently published a document which includes some guidance with regard to a barricade vs. a door locking device. Item 1 on this list reads (in part): ”Door Locking Devices are subject to Approval. According to the fire code, ‘Security devices affecting means of egress shall be subject to approval of the fire code official.’ Ensure that any application of a door locking device is not in violation of the fire code. A door locking device accepted by one fire marshal may be rejected by another jurisdiction.”

It’s also important to look at the frequency of lockdowns in schools across the country. If a lockdown plan includes the use of barricade devices on the classroom doors, the devices could be installed for extended periods of time whether the danger is inside the building or somewhere in the vicinity. A search of the national news found the following lockdown incidents reported for 1 day – March 19, 2015, each involving 1 or more schools.

- Baltimore, Maryland – loaded gun in school

- Norwich, Connecticut – false report of gun in school

- New Stanton, Pennsylvania – man shot at home

- Cumming, Georgia – teen trespassing on campus

- Greenville, North Carolina – man with gun reported by children

- Cameron Park, California – mountain lion sighted

- Kimball, Minnesota – armed person possibly in area

- Coraopolis, Pennsylvania – domestic dispute related threat

- Charlotte, North Carolina – search for robbery suspects

- Dowagiac, Indiana – bank robbery in the area

- Elkhart, Indiana – report of gunshots nearby

- Atlantic City, New Jersey – fight inside of school

- St. Paul, Minnesota – police activity in the area

- Union Springs, Alabama – child taken from bus by relatives

- Port Angeles, Washington – search for escaped prisoner

- Bowie, Texas – stolen car chase and footchase

Code Considerations

Given the increased focus on school security, the discussion about using a barricade device or alternative method to secure a classroom door has likely taken place with code officials in every state. A set of guidelines published by the National Association of State Fire Marshals (NASFM) includes a Suggested Classroom Door Checklist, which identifies many parameters that should be satisfied when selecting and installing hardware intended to increase classroom security:

- The door should be lockable from inside the classroom without requiring the door to be opened.

- Egress from the classroom through the classroom door should be without the use of a key, a tool, special knowledge, or effort.

- For egress, unlatching the classroom door from inside the classroom should be accomplished with one operation.

- The classroom door should be lockable and unlockable from outside the classroom.

- Door operating hardware shall be operable without tight grasping, tight pinching, or twisting of the wrist.

- Door hardware operable parts should be located between 34 and 48 inches above the floor.

- The bottom 10 inches of the “push” side of the door surface should be smooth.

- If the school building does not have an automatic fire sprinkler system, the classroom door and door hardware may be required to be fire-rated and the door should be self-closing and self-latching.

- If the door is required to be fire-rated, the door should not be modified in a way that invalidates the required fire-rating of the door and/or door hardware.

The NASFM guidelines also note that although the word “should” is used in the checklist, these requirements may be mandatory depending on applicable codes, laws, and regulations. The International Building Code (IBC), International Fire Code (IFC), and NFPA 101 – The Life Safety Code have been adopted in most states, and these 3 publications include the egress, fire, and accessibility requirements in NASFM’s checklist. These model codes are revised on a 3-year cycle in order to take into account changing environments and new technologies, using a consensus process with careful consideration by technical committees and ample time for public comment. States and local jurisdictions may modify these codes, so it’s very important to be aware of the local code requirements, including the jurisdiction’s position on barricade devices.

The NASFM checklist parameters for a) classroom doors to be lockable from inside the classroom without opening the door, and b) classroom doors to be lockable and unlockable from outside the classroom, are not currently included in the three model codes referenced above, but code change proposals have been submitted by the Builders Hardware Manufacturer’s Association (BHMA) which will add these requirements if the proposals are approved. The prescriptive requirements included in the model codes ensure that requirements for free egress, fire protection, and accessibility are met, in addition to providing adequate security.

Local Jurisdictions

Many code officials have responded to questions about school security by reiterating that egress doors (including classroom doors) must meet the requirements of the adopted codes. The model codes may be modified locally, which could make the local requirements less stringent (for example, allowing one additional operation to unlatch the door) or more stringent. Some states, such as Florida and California, have already adopted requirements or guidelines for classroom doors to be lockable from the inside, with classroom security locks being the preferred lock function. For these states, the local guidelines are more stringent than the current model codes.

Many code officials have responded to questions about school security by reiterating that egress doors (including classroom doors) must meet the requirements of the adopted codes. The model codes may be modified locally, which could make the local requirements less stringent (for example, allowing one additional operation to unlatch the door) or more stringent. Some states, such as Florida and California, have already adopted requirements or guidelines for classroom doors to be lockable from the inside, with classroom security locks being the preferred lock function. For these states, the local guidelines are more stringent than the current model codes.

In some jurisdictions, there is political pressure to relax the code requirements in favor of approving the use of barricade devices, even when code officials oppose the change. Lawmakers in Ohio have filed bills “To amend section 3737.84 and to enact section 3781.106 of the Revised Code to require the Board of Building Standards to adopt rules for the use of a barricade device on a school door in an emergency situation and to prohibit the State Fire Code from prohibiting the use of the device in such a situation.” In Arkansas, the state fire marshal voiced strong objections to a Senate bill that would amend the fire code requirements and allow the use of barricade devices in schools, noting potential issues with emergency egress and removal of the device. The Arkansas Senate voted unanimously to approve the fire code change, despite the fire marshal’s objections.

Other states have independently issued directives or adopted code changes which vary from state-to-state. For example, Colorado has adopted a code change that allows temporary security measures only until January 1, 2018. The State Fire Marshal in Kansas issued a memo allowing temporary security devices to be used, Louisiana allows a deadbolt that requires one additional operation to unlatch the door, and New Jersey permits some types of devices but not others. These policies lack consistency from one state to the next. A more efficient and effective approach would be to incorporate school security requirements into the model codes used across the country, utilizing the expertise and experience of code officials and others who are knowledgeable about all aspects of the issue.

Other Potential Consequences

In addition to the code considerations, another concern is that barricade devices can be used by anyone who has access to them, including someone who wants to barricade him- or herself and others in a room in order to commit harm or take hostages. Addressing this possibility by storing the device in a locked drawer or in a location known only to the teacher could result in a delay in installing the device at a critical time, and a substitute teacher may not have the means or knowledge to secure the door.

In addition to the code considerations, another concern is that barricade devices can be used by anyone who has access to them, including someone who wants to barricade him- or herself and others in a room in order to commit harm or take hostages. Addressing this possibility by storing the device in a locked drawer or in a location known only to the teacher could result in a delay in installing the device at a critical time, and a substitute teacher may not have the means or knowledge to secure the door.

Although every school shooting is tragic and we must do all we can to prevent them, these events are rare; nonfatal victimizations at school are thousands of times more likely to occur, and unauthorized lockdown of a classroom could help to create a haven for someone attempting to commit a crime. According to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES):

- “In 2012, students ages 12–18 were victims of about 1,364,900 nonfatal victimizations at school, including 615,600 thefts and 749,200 violent victimizations, 89,000 of which were serious violent victimizations.”

- “During the 2009–10 school year, 85 percent of public schools recorded that one or more of these incidents of violence, theft, or other crimes had taken place, amounting to an estimated 1.9 million crimes.”

- “During the 2011–12 school year, 9 percent of school teachers reported being threatened with injury by a student from their school. The percentage of teachers reporting that they had been physically attacked by a student from their school in 2011–12 (5 percent) was higher than in any previous survey year (ranging from 3 to 4 percent).”

In addition to the negative impact on egress, most barricade devices prevent access from the outside, so even a staff member or emergency responder with a key would not be able to enter. While there is debate on whether or not barricade devices should be allowed for use, schools should also consider their liability in using such devices. What if a barricade device was used by an unauthorized person to secure a classroom and commit an assault or other crime, leaving staff and/or law enforcement unable to access the room because of the device?

Don’t Take My Word For It

With a classroom security lockset, a staff member with a key can lock the outside lever without opening the classroom door. The inside lever always allows free egress. An indicator on the lock gives a visual indication of the door status. Photo: Schlage

There are many publications which address recommended locking methods for classroom doors, the need for code-compliance, and support for incorporating school security requirements into the model codes. None of the following include recommendations for installing secondary locking devices:

- The final report of the Sandy Hook Advisory Commission includes many recommendations for school safety, including Recommendation #1 – classroom doors should be lockable from inside the classroom. The report states: “The testimony and other evidence presented to the Commission reveals that there has never been an event in which an active shooter breached a locked classroom door.” There are other factors to consider, such as impact-resistance of glass adjacent to door hardware, distribution of keys to all staff including substitute teachers, methods of securing exterior doors, protocols for visitors, as well as procedures, communication, training, and drills. Barricading of doors is not mentioned in the Commission’s report.

- FEMA-428 – Buildings and Infrastructure Protection Series Primer to Design Safe School Projects in Case of Terrorist Attacks and School Shootings (2012) states that all locks on egress doors in schools must comply with the requirements of NFPA 101 – The Life Safety Code. The FEMA publication also discusses the importance of lockable classroom doors: “While the interior locks on classroom doors saved many lives at Columbine High School, they were not available in classrooms in Norris Hall at the Virginia Tech campus. Although attempts were made to barricade the doors with furniture or live bodies, they were not successful and the death toll was much greater.”

- The International Fire Code Commentary is a companion publication to the IFC, and includes a section addressing lockdown requirements. The 2012 IFC Commentary for section 404.3.3 Lockdown Plans, reads (in part): “Note that the code does not require a lockdown plan; however, if a lockdown plan is developed, it must be strictly supervised in order to maintain occupant safety at an acceptable level. Many facilities are adopting procedures that can significantly affect fire and life safety, such as using the fire alarm system to signal a security emergency, locking doors with devices that prevent egress in violation of the provisions of Chapter 10 of the code, and chaining exit discharge doors from the inside to prevent occupants from leaving the building. It is important that plans for security threats do not include procedures that result in violations of life safety and actually increase the hazard to the occupants.”

- The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regulation 1926.34 prohibits devices that impede egress: “No lock or fastening to prevent free escape from the inside of any building shall be installed except in mental, penal, or corrective institutions where supervisory personnel is continually on duty and effective provisions are made to remove occupants in case of fire or other emergency.” In some states, OSHA regulations do not cover state and local government employees (including school staff), but many states adopt the OSHA regulations as part of their workplace safety requirements. In those states, the OSHA requirements for free egress may apply to schools.

- Some proponents of barricade devices have suggested that it is safe to relax the code requirements addressing fire protection because fatal school fires are no longer common. The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) reports that, “U.S. fire departments responded to an estimated average of 5,690 structure fires in educational properties in 2007-2011, annually. These fires caused annual averages of 85 civilian fire injuries and $92 million in direct property damage. An average of one death occurred in daycare properties” (NFPA Structure Fires in Educational Properties Fact Sheet). Any one of these fires could have been tragic, as fatalities in school fires were not uncommon before the codes were put in place and enforced. Although it has been more than 55 years since 95 lives were lost in the fire at Our Lady of the Angels School in Chicago, it seems likely that the strength of current codes and enforcement have played a role in the improved safety of our schools.

- In the March/April 2015 issue of NFPA Journal, Ron Coté notes that guidelines do not exist currently that would “allow a classroom door to be locked against opening from the corridor side while still ensuring the door can be opened by any classroom occupant, or that emergency responders can access the classroom in time to prevent an occupant from causing harm to those within the room.” In December of 2014, NFPA held a two-day school security workshop, attended by more than 60 stakeholders. The purpose of the workshop was to look at issues affecting schools as they balance security with fire and life safety, and to propose solutions to those problems. Upcoming meetings of several NFPA technical committees are expected to discuss provisions for blending school security with fire safety, which could lead to changes in the 2018 edition of NFPA 101.

Conclusion

The instinctive reaction to the fear surrounding school shootings is to do everything possible to protect students and teachers from being in the line of fire. The desire to react quickly and within budgetary restrictions sometimes leads to choices that may solve one problem but inadvertently create others. The requirements for free egress, fire protection, and accessibility must be considered in conjunction with the need for security. Unauthorized lockdown and emergency responder access are important considerations, although not currently addressed by the model codes.

One option for classroom doors is an electrified lock that can be locked by pushing a button on a fob worn by the teacher. Photo: Schlage

Changes made to codes or laws at a national level would establish more consistent requirements than addressing this issue individually. When a jurisdiction chooses to modify the model codes, requirements should be prescriptive and an all-hazards approach should be taken, considering not just active shooters and terrorism, but also fire, severe weather, natural disasters, and other types of emergencies.

The reasoning behind proposed changes is often based on the misconception that barricading the door is the only way to protect students and teachers in the classroom. There are code-compliant locks readily available from many lock manufacturers which provide the needed security without compromising safety in favor of lower cost. While locks address one aspect of classroom security requirements, there are other factors to consider, such as the door, frame, glass, key distribution, communication, and lockdown procedures.

Many school security experts recommend classroom security locks, which can be locked from within the classroom using a key (mechanical locks) or electronic fob (electrified locks). Other lock functions can also be used, depending on existing conditions, the needs of the facility, and the budget. All lock functions that would typically be installed on a classroom door allow free egress as well as authorized access by staff and emergency responders, and will provide the necessary balance between the security of teachers and students within the classroom and safety for a range of hazards that may occur.

A follow-up post by Lieutenant Joseph Hendry on the unintended consequences of addressing security without considering life safety is published here.

No exit graphic: ©iStock.com/MirekP, corkboard: Thinglass/Shutterstock.com, question marks: ©iStock.com/NorthernStock.

You need to login or register to bookmark/favorite this content.

Those who can must do anything and everything to protect the children and staff no matter what that is during the incident. However, what we all do to plan for incidents must comply with the fire code in every single instance and at every single door without any exception. There is no Earthly reason that all doors in a school should not be lockable from inside each defensible space while still allowing free egress from that space by using a remote system or key. That goes for the millions of people we have so sadly and wrongly placed in very vulnerable trailers outside the defensible perimeter of our schools. Those children and staff are treated as second class citizens where security is concerned and it is a national shame.

We could easily develop a barricade device that could be secured in a holding device only accessed thru the use of a key or card fob to release the device in the event of an emergency. This like the use of classroom security locks which require the use of a key to lock or block entry from the outside in my mind is not a logical way of securing the door. In most cases I have to imagine the situation is very stressful, thus requiring the teachers to have the ability to have their keys within reach at the moment they need to have them and then have to fumble around trying to get their keys in the lock cylinder is a very difficult process considering what would be going on around them. Simply put install a entrance function lock. turn the knob from the inside, door is locked from the outside. no complicated steps to take.

The problem with a Entry function is that anyone can lock the door and in situations with young children they could lock the door if a teacher were to step out in the hallway. If that teacher did not have her keys with her that situation could escalate depending on the age of those children. This is why the Intruder function was developed and in my opinion is the best solution for classrooms.

Very well written. I agree that codes should be nationally written and enforced. Of course I’m in California and we already have stricter guidelines. I don’t like the idea of barricades. Too many “what if’s” are possible. Most notably the possibility of someone in the room locking everyone out to commit a crime or violent act. Classroom security locks have become a large issue in our area, out of fear of what could happen. But the schools are slow to change the locks, usually noting costs. There are some less expensive options. But when we are talking about 20-50 doors its going to be expensive. Most school districts just don’t have the funds for this.

Thank you for addressing this subject so thoroughly!

The locks may be expensive but how expensive is that lawsuit going to be when something “bad” happens behind that barricade?

Lori,

This article is very well written and thought provoking. Unfortunately i suspect it is going to take something severe occurring inside one of these barricaded classrooms before legislators begin to understand the damage being done by overruling code officials and Fire Marshals opinions. I have looked at several of these devices and I see nothing but a potential disaster if they are used. This appears to be a situation where the needs of the few may outweigh the needs of the many. No one can dispute that the codes we live with today have saved many many lives over the years. Authorizing these barricade devices will only succeed in creating more situations where are children are unsafe. If we as a industry do not make our voices heard and speak to our legislators then we will become part of the problem rather than the solution. Thank you for continuing to address this issue.

Its hard to get around a properly installed and setup mortise lock, or even cylindrical. I think a means to lock the door from the inside (for a school, the thumbturns inside don’t work well for teachers who will get locked out by students) that requires a key is probably best. Egress is a concern, and the cost for schools to re-install panic devices on all classroom doors could be prohibitive.

For the most part, I can’t see a shooter effectively shooting his way through a locked door when there are other easier means to gain entry elsewhere.

Great article Lori! Hits on all the points. Obviously, many people believe their infrastructure is inappropriate for the use of lock down as a response. These devices acerbate the problem. What really needs to happen is infrastructure codes need to be updated to include AS/Terrorism concerns with a focus on evacuation, not lock down, as a primary response. Fire has been doing things the right way for around 120 years. Throwing out the codes is shortsighted in the extreme.

Hey Lori,

I think it is very well written. I too agree that codes should be nationally written and enforced.

Thanks as always!

We need to make sure that the school administrators contact the local fire marshal or chief before they make any changes or if they find out that any of the school’s parent groups are collecting money to buy additional security that they are informed that it has to meet everyone approval. I have three school districts and large number of church based schools. Today I contacted one of the administrators that I deal with on any projects that are going on, and next week after the other two districts come back from spring break that I will be talking to them as well as the individual church based (mostly catholic) schools. Public Education is the Key.

Well said Lori! I agree with your paragraph in the conclusion that NATIONAL changes to codes or laws would be the best way of addressing this problem. I believe that is the only way we can be sure the classrooms are safe from intruders, while also safe from a threat within the room. Barricades scare the heck out of me. We in the hardware biz need to lobby for National guidelines.

A lot of very good information, Lori. And very well-written. The points you make are clear and succinct, and will be easily understood by those outside of the door & hardware industry.

I agree with the others that the standards governing classroom safety should be national. And also that, as national standards, they should not be open to interpretation or modification by individual states.

It sometimes seems almost comical… the educated minds advising to barricade a classroom door from the inside during a “situation”. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a classroom door that swings into the classroom, so it would be interesting to have these promoters of such nonsense provide a live demonstration for us.

And these well-intended minds who have dreamed up these barricade contraptions should be thanked for at least trying to solve the problem, but that’s about as far as it goes. The only logical thing to do is use common sense and proven door hardware… classroom security locks- either manual or electronically by fob.

Lastly, I believe security should also be focused at the entrances and visitor clearing areas with bullet resistive steel doors and frames, electric hardware and camera & intercom type communication, and making sure that the staff is regimented adequately in all procedures. That would be an effective and sensible solution. And really, there has to be a sensible balance of safety and security otherwise, we must build our schools just like prisons.

Hi Lori:

It’s not rocket science, I’m a nationally certified Fire/EMS Safety Officer and we have the same problems, do you make a school safe for the 1/1,000,000 crazy or make it unsafe from someone using the barricade device 1/1000. In the fire service you have firefighters who want to go inside, even though the building is made with engineered lumber, which is low-cost and extremely strong but fails in a fire within 20 minutes and you don’t know when the fire actually started, another good article, thanks

Difficult subject with too many knee-jerk reactions proposed (Arkansas what are you thinking?! Disregarding your own State Fire Marshal?!). If it were my kids in these classrooms, I’d be more worried about an “inside job” where the terrorist/gunman is a student inside the classroom keeping all the authorities out. Key distribution? As soon as a gunman puts his gun to a teacher’s head and says give me your keys, do we really think key distribution will do any good?

Great job on the article. You stayed neutral, presented facts and information, made it understandable, and presented the dilemma clearly for all to ponder.

Well written and informative for the intended scope of Doors & Hardware. I first wondered about the definition of “classroom security locks” but only needed to look at the illustration at the side of the text for clarification. I did wonder if the article will be footnoted with a reference for the “guidelines published by the National Association of State Fire Marshals (NASFM)”.

Hi Kenneth –

I will ask the editor of Doors & Hardware if she has enough space to include references to all of the resources that I posted, but I just added a link for the NASFM document to the article. I will add the other links when I have a minute.

– Lori

“749,200 violent victimizations, 89,000 of which were serious violent victimizations” – enough said. I see these barricade devices being used initiate such victimizations and causing many more problems than they solve.

Lori, I work at a university, and have been involved in numerous discussions regarding classroom security and appropriate hardware selection. Recent construction has employed use of mortise deadbolt locks, both mechanical and electronic, with the goal of providing the ability to shelter in place and allow authorized emergency responder access via key or elevated card privilege. Your article covers virtually every argument/discussion I have encountered, and the references you cite are extremely helpful. I find the article very well written, and intend to use it as an educational aid for those willing to overlook the hazards associated with non-code compliant solutions. I am very fortunate that our local code officials have taken the time to work with me in developing and approving hardware solutions which both increase occupant security and meet fire safety regulations, but your article will help as I explain the restrictions and limitations to those seeking protection – teachers, staff, and students. Thanks!

I am not exactly a good witness for this debate as the father of a first year elementary teacher, my daughter. I strongly believe any means should be used to protect students and faculty from harm in an active shooter incident. I believe teachers and faculty can be easily trained to use barricade devices and to secure the devices from student tampering. It’s not as if you would leave the devices in plain site, for many reasons. I’m afraid some AHJ’s might feel like their status is being threatened because schools want to use a device IN A DESPERATE SITUATION ONLY and not to over-ride any safety measures that are normally in place. A police officer has their weapon strapped down until it is needed to stop or prevent a bad situation from happening. The barricades can be guarded in the same manner. OK, off my soapbox now.

I appreciate your comment, Leonard. I have kids in school and I want their teachers to be able to protect them, but I’m much more comfortable with a method that the teacher can control. I don’t like the idea of someone being able to lock the door and have nobody able to get in or out. And unfortunately, the barricade devices are often mounted right next to the door.

Some read through’s

“Barricading uses gross motor skills, is “”. Maybe a different word than gross

“about llllschool security by reiterating”. Typo?

Great article

I am not sure that it should be added to the building codes. One problem is technology and building design changes, and the codes have a hard time keeping up.

You use the term “fire protection ” maybe a sentence or two explaining why the correct door operation is needed.

Thanks Charles! I couldn’t change gross motor skills because fine and gross are the defined terms for motor skills, but I fixed the typo and added something to help clarify egress, fire protection, and accessibility.

It is really about acceptable risk.

The concept of having available any article, barricadce, or device that can be mis-used, just makes no sense to me. If having something that could cause potential harm to those INSIDE of the door is the price to pay for additional security, then the price is too high.

Well thought out solutions, that can be used in only the appropriate way, are useful and acceptable. Solutions that increase risks should not be allowed (by code).

Decisions on any safety matters need to be made on a well-reasoned risk analyst, include cost verse benefit, not on the emotion of the time or a single hazard.

Care should be used in statistical reasoning when completing the risk analyst, as statistics can be skewed to support the argument the position author of the study or the user wishes to advance.

In my opinion the risk analyst for any issue in the build environment needs to provide safety from a reasonably anticipated event that has higher probably of happening than the outlying event that has a low probably of happening. Is it more likely that a fire or assault on a student or teacher will happen in a class room, over single or multi person attacker in a school building?

I believe the fire and assault are more likely and therefore should be given the priority in safety by allowing the door to be freely opened from the inside. I believe that the use of barricade devices, chains, cables or the various door stops now available are more of a hazard to the more likely events that do happen in schools.

The low cost fixes being proposed should not be entertained when the lock and hardware industry have develop products that allow a room to be locked from the inside to prevent entry for the outside, while allowing for the free exiting from the room and provide a unlock function from the outside for supervisory or emergency personnel to enter the room as needed.

While the proper fix maybe more expensive they are code compliant, as they offer protection from the reasonably anticipated emergencies while offering an extra level of protection to the low frequency attacker in a school building.

Student Lives Matter

I think these “inventors” have good intent. They simply aren’t aware of the codes that govern doors/hardware. I know it seems like common sense but how many times have those of us in the industry tried to explain what we do to an outsider just to hear them say, “I had no idea so much went into doors”. These inventors are trying to come up with a way to protect our kids (with hopes of getting rich in the process). I’m assuming they aren’t aware of the dangers they create with these new products.

I’m well aware of the codes and I understand the need for emergency egress, emergency access, etc. I’ve also heard that locked doors are rarely breached by active shooters. However, as a parent, I would like to see something a little more substantial than a 1/2″-3/4″ throw latch-bolt protecting my child. How many times have you seen a gap between the door and frame that is greater than 1/8″? That means the latch is offering less protection than intended. Are you comfortable knowing that there is only 3/8″ of metal keeping that shooter from breaching the classroom door? It’s likely less than that. It’s probably only a 1/4″ piece of glass preventing a reach-in and quick turn of the lever. I’m not comfortable with that.

I believe our schools and classrooms deserve an extra level of protection in an active shooter situation. Unfortunately, I don’t have an answer for how to achieve that. I may feel differently than most of you in the industry when I say I’m not opposed to something that would add security even if it does require one additional step to egress. As long as it can’t be deployed by anyone (students, outsiders, etc.) and still allows authorized access from the outside, I think it’s worth it for our kid’s safety.

Just a thought:

Maybe there should be a new code that states ALL classrooms must remain closed and locked when occupied (not too much of an inconvenience, right?). That provides the first layer of security by eliminating the need for a teacher to fumble for the key in a very tense/scary situation. If the door is already locked, there is an immediate sense of security for everyone. Now the kids can be directed to their hiding places and the teacher could make his/her way to the door to engage a double-cylinder deadbolt with a 1″ throw. This deadbolt would only be allowed to be locked in an active threat situation. Maybe it could have a special housing or big RED trim ring with a built-in warning that reads “Emergency Use Only”. The teacher would have the key and it would also be accessible from the outside should it be locked inappropriately. The deadbolt prevents the shooter from being able to break the glass at a narrow lite window and gain access (which can happen with a standard classroom lock). I don’t think the extra time it takes to open that deadbolt would be an issue in most active shooting circumstances. The likelihood of a fire or other life threatening emergency taking place in the classroom during an active shooting event is minimal.

Our kids are special. There are already special considerations for other applications such as mental facilities. There are special considerations that allow double-cylinder deadbolts if there’s a sign that reads “door to remain unlocked during business hours”. Why can’t there be special hardware considerations for classrooms?

I’m ready to be bombarded with all of the objections. But please include in your response whether or not you have kids of your own that are still in school.

Eric T, many of these devices are easily compromised, marketed as being stored next to the door and require more than one step for installation.The videos for installation are posted on the internet. The fact that most of the threats in education are students or staff, the use of these devices allow the threat access to securing the class room and preventing entry. They fail to address what occurs when staff may not be with students or, unfortunately,staff may have been injured. They fail to address what happens in other locations in the building. They fail to address the man sized windows in doors or next to them.

The real problem is that our infrastructure and training have allowed the threats to get a 20 year head start in planning.Attempting to build a response around single option response lock down leads to concept failure. Any process of installing a secondary locking device requires fine motor skills that fail under times of stress. A teacher can not locate their key, nor can they insert it into a lock when I put them under minimal stress in training. Along come these companies who develop a product that requires several different movements and the fine motor skill of placing devices under doors, into slots, turning handles, etc. Those skills under stress disappear. Fire Training figured that out 119 years ago and now some are trying to throw out the hard earned lessons, paid in lives, from past mistakes.I can not find one device on the market that has been independently tested for reliability or application under stress. That should concern all of us.

The actual change we need to be implementing is changing infrastructure to allow for safer evacuation from our facilities for terrorist/active threat events. In fact, that is the primary recommended response from the Federal Government and my State (Ohio) and the ALICE Training Institute. We need code enhancement so it requires better doors, better walls, and better locking systems (contained within the door frame at multiple points and none of them are in the floor!)that remove any requirement of the use of fine motor skills during a crisis. Just like we have with life codes and fire.

These devices are the equivalent of lipstick on a pig. The real problem is that we have failed for twenty years to plan and adapt to the threats and have relied on turning off the lights, not moving, pretending we are invisible, relying on a single door lock or window, and having no plan for contact, in a single location, in buildings in which every room is occupied. No device is going to solve that problem. Better infrastructure and more training are the real answers.

I have three children, all at different levels of the educational system.I also teach and train in mental facilities, K-12, hospitals, universities, business and industry. If you would like to see my background, I’m on linkedin. I know Lori thinks about her own children, as do I and you and everyone in the country. Doing things the right way is the best way and we do that by addressing the issue for the long term, not just trying to quick fix it. That’s how we got lock down in the first place.

The picture I took of my son’s school from a few years ago gives me chills every time I see it and think the gym was full of students, teachers and parents and this wasn’t the only locked exit door at the school. Note that this wasn’t the main exit doors for the gym, all the doors on the exterior of the school with panics were chained in this fashion. Imagine if the gym exits were blocked by fire and we were forced towards the chained exit doors.

Thanks Wayne. With regard to chains or other locking methods that are supposedly used only “after-hours”…what about firefighters who may enter the closed and locked building, who need to exit through a different door in a hurry?

That’s very true Lori and something I didn’t think about. The firefighters would be trapped as well. It seems the school is more worried about security of property than safety of people. Code officials and professionals like myself need to continually remind the school districts and community of these issues. It takes vigilance on my part as we’ve discussed before. Once is definitely not enough.

Great article. I am a locksmith for a school district in New Mexico and the teachers/principals/etc. are really pushing for these barricade devices. In fact, my three children that attend elementary school all came home with a letter asking for a $40 donation per child for these devices.

I can understand the concern but I must say that I have witnessed first hand and for many years now how irresponsible some teachers can be with their keys. They leave them out in the open on their desks, leave them hanging in the cylinder, give them to kids to fetch things for them, etc. Which leads me to believe that even being able to lock from the inside is going to be a challenge. I propose a locked door policy, meaning your door is to be closed and locked at all times, period. Also, maybe even installing storeroom levers on classroom doors so that you must always use your key to open the door. I just seems the simplest to way to eliminate the issue of having to open the door and secure the lock.

I appreciate this wonderful article and will be sharing it with my supervisors.

Thanks James! There is more information on my Schools page – http://www.iDigHardware.com/schools. There might be something there that would help you.

Does the New Mexico State Fire Marshal allow classroom barricade devices?

– Lori

Allowing fire marshals the final say may be counter productive in protecting people in classrooms. Tell me the last time a person was killed in a school fire, versus some type of criminal activity in the school. Many barricades are nothing more than a piece of metal which slips into the bottom of the door and into a frame secured to the floor to supplement the door knobs. These are easily placed on and off and can allow for any swift egress. What teacher is going to lock the door if the fire alarm goes off?