Something is draining the battery on our 12YO Honda Pilot. After a full investigation on YouTube, I told my husband that I suspected a faulty AC relay. His suggested workaround…roll down the windows and stop using the air conditioning. How does this relate to classroom barricade devices? Read my next Decoded article (below) and find out…

This post will be published in the May 2019 issue of Door Security + Safety

After working with door openings and the related life safety code requirements for over 30 years, and spending the last 5 years even more focused on advising school districts and other stakeholders on how to keep school security safe, I had to step back and ask myself some questions:

- Why would a school district consider using security devices that are not compliant with the model codes or accessibility standards, given the associated risks and liabilities?

- Why is the potential for unauthorized lockdown being ignored, when nonfatal victimizations and other crimes in school classrooms are hundreds of thousands of times more likely to occur than a school shooting?

- Why has the perceived need to lock building occupants inside of a room replaced the established need for safe egress and evacuation, especially when barricading has been used to delay emergency responders during past school shootings?

- Why has this become a battle of law enforcement vs. fire marshals, state legislators vs. code officials, and code-compliant security products vs. unregulated barricade devices, when traditional locksets provide the needed level of security?

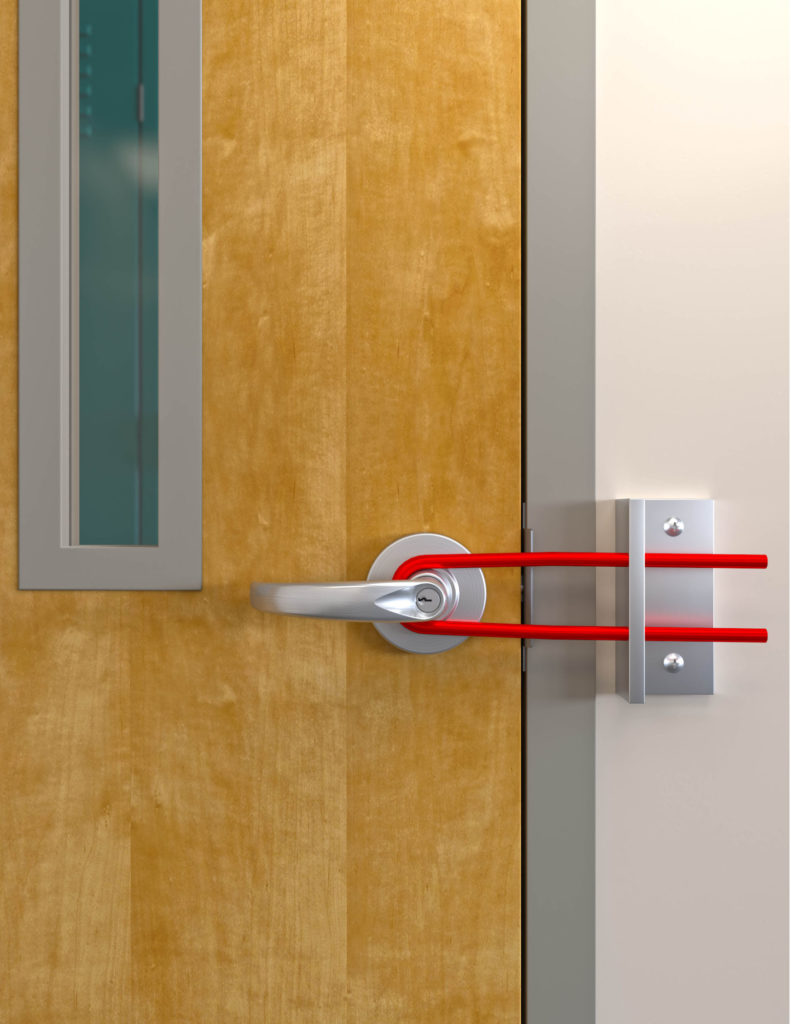

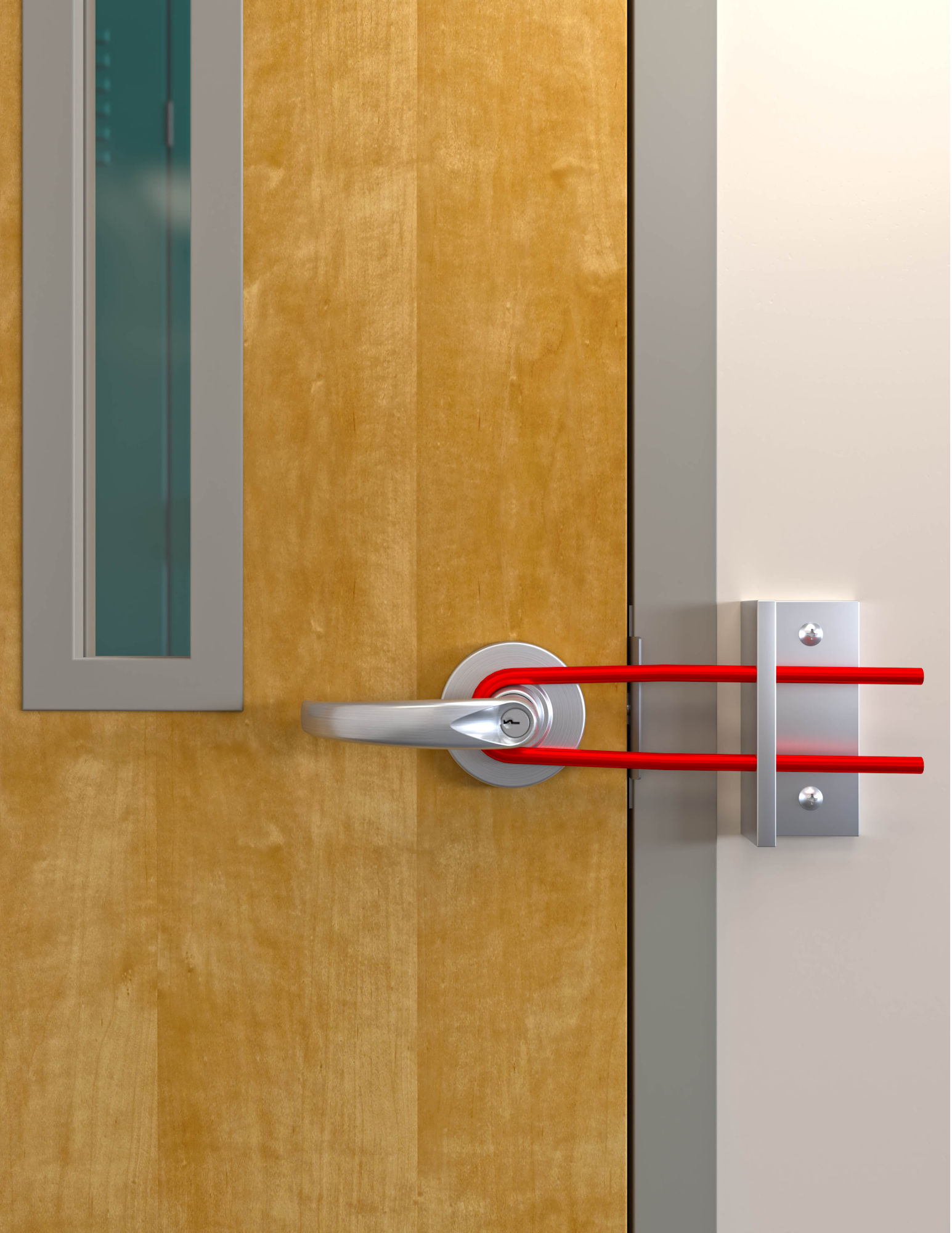

Although it may be tempting to fabricate inexpensive security devices in a high school metal shop class or purchase retrofit devices online, there are multiple safety concerns regarding these methods.

You might think the answer to these questions has to do with cost. In my opinion, the answer is related to complexity. Traditional security products – locksets and panic hardware – are complicated. To most architects, a door hardware schedule looks like hieroglyphics. When I meet with a security consultant or integrator, everyone else in the room thinks we’re speaking another language. There are dozens of lock functions, various types of locksets and panic hardware options, not to mention electrified hardware. When faced with the task of puzzling through the existing hardware on classroom doors to determine how to improve security, it may seem easier to order a retrofit security product online or have bent bars fabricated in a high school metal shop class and placed in each classroom for the teachers to use when necessary.

This is not unlike the workarounds that have become so common because of the widespread use of technology in other areas of our lives. When the left mouse button on my computer stopped working, I bought an inexpensive wireless mouse, plugged the receiver into my USB port, and was back in business in minutes. When a setting on my smart phone affected the headphone jack, I bought some cheap Bluetooth headphones. When I couldn’t figure out how to use our fancy new video conferencing system, I called into meetings the old-fashioned way. We are conditioned to find a workaround, especially when time is of the essence and money is tight.

I do understand the motivation to employ the unregulated security products or bent bars made in metal shop class, but I was initially unprepared for the legislative workaround that has occurred in several states. The model codes used across the US are created by a consensus process involving hundreds of stakeholders and based on more than 100 years of experience – often tragic events and hard-earned lessons. I’ve been surprised by the bills I’ve seen in several state legislatures which remove all of those safeguards, and even more bewildered when a fire marshal considers overriding the adopted model codes – just so a school district can purchase classroom barricade devices or have the shop class start bending bar stock.

Which brings me back to the original question – “Why would a school district consider using classroom barricade devices?”

I have seen many comparisons from manufacturers of barricade devices, between a traditional lockset at $500 vs. a barricade device at $150, for example. Given the pressure to “do something – anything – and do it now!” this seems like an easy decision. A few PTA fundraisers and some classroom doors sponsored by parents, grandparents, and community members, and the problem appears to be solved. In theory, a school district could spend $150 per classroom on a classroom barricade device (or much less on the shop-fabricated version), that can be procured quickly and installed easily, rather than spending a lot of time and money to buy and install a new lock.

The problem with this comparison is that almost every classroom door already has a lockset or panic hardware. In many cases, a new $500 lock is not needed in order to reliably secure the classroom door – the lock is already there, and locksets and panic hardware are certified to ensure security and durability. Maybe school staff members do not have keys to the existing locks – this can be resolved for a minimal cost, even if the locks need to be rekeyed. If the existing lock function is not ideal for today’s security threats, some locks can be upgraded with a conversion kit to change the function rather than replacing the entire lock – often at a lower cost than purchasing a classroom barricade device. Where glass in vision lights and sidelights adjacent to the existing hardware causes concern, there are films or replacement glazing products available which increase the impact resistance.

Deadbolts installed in addition to existing hardware can lead to delayed evacuation and unauthorized lockdown, and may also be more costly than upgrading existing locks, addressing adjacent glazing, and/or distributing keys.

When a school district decides to completely replace their existing locksets, it is often because they are long overdue for an accessibility upgrade, the existing locks are beyond their usable lifespan, or because of a desire to add electronic access control and remote lockdown functionality. But a complete lock replacement is not required for most schools and should not be used as the typical comparison. I have also seen added deadbolts suggested as an alternative, but in addition to requiring more than one releasing operation to unlatch the door (not allowed by the model codes), installing deadbolts can be much more expensive than rekeying or using a conversion kit to upgrade existing locks.

We can help.

As members of the door and hardware industry, we have relationships where we help to ease the complexity and pain points associated with traditional hardware. We work with architects and specifiers to provide detailed hardware specifications for new projects and renovations. We coordinate with security consultants and security integrators when electronic access control is involved. We are available to facility managers and locksmiths when there are problems with existing openings. What we don’t always have is a connection with the school administrators charged with making decisions about their school’s security.

It’s our responsibility – as experts in both security and the codes that ensure life safety and free egress, fire protection, and accessibility – to offer our expertise to school districts looking for answers. We can assist school administrators, teachers, parents, and students with information about how their locksets function, and suggest improvements if needed. We can reach out to code officials, law enforcement officers, state legislators, and state boards of education to help keep their state and local security requirements safe. We can use lessons learned in past events to guide future decisions, and make sure the implemented security methods comply with adopted codes and laws.

Get involved. Share your experience. Keep school security safe.

~~~

When evaluating a security method to determine whether it is safe and code-compliant, here are 6 questions to ask:

- Does the door unlatch with one releasing operation? Current model codes require one operation to release all latches on the door simultaneously.

- Can the door be opened for egress without a key, tool, special knowledge, or effort, and without tight grasping, pinching, or twisting of the wrist? When it’s time to exit, a building occupant must be able to open the door without wasting valuable time trying to find a key or remove a security device that is not intuitive.

- Is the releasing hardware mounted between 34 inches and 48 inches above the floor, or in the location required by the state or local codes? This requirement ensures that all building occupants – including children as well as people using wheelchairs – can operate the hardware for egress.

- If the door is a fire door, is the locking/latching hardware compliant with NFPA 80 and listed to UL 10C / NFPA 252? This listing ensures that the product is suitable for use on a fire door assembly, and that it will not negatively impact the performance of opening protective.

- Can the retrofit security device be deployed without attaching to or modifying the existing panic hardware, fire door hardware, or door closers? Retrofit devices attached to existing hardware may impact the listing and/or performance of the hardware, and often rely on the strength of fasteners and connections that have not been tested for this purpose.

- Is it possible to unlock the door from the outside with a key, credential, or other approved means? It is critical for school staff and emergency responders to have access to classrooms from the outside, in case an unauthorized person secures the door in an attempt to commit an assault or other crime.

You need to login or register to bookmark/favorite this content.

You’ve probably answered this in a previous post but I have to ask: why are building codes referred to as “model codes”?

Hi Eric –

The model codes are models for states or local jurisdictions to adopt – either as-is or with modifications which make them more suitable for the unique needs of that jurisdiction.

– Lori

As an industry, we should have gotten out in front of this issue long before the frustrated public had to find their own solutions. I believe we failed in our roles as security and life safety experts, and now we’re faced with trying to combat this issue with a much more expensive (although proper) solution. If the cost is minimal, perhaps the conversion kits could be (or should be) made for all modern-era locksets and promoted to school districts. These conversion kits could be provided at a cost that makes this the obvious choice for school districts. As I have traveled with reps through the years, they could easily identify what lock platform each school district used. It would give the local rep the opportunity to be part of the solutions and gain back the trust of the public.

Michael, I think you are looking at this from the wrong perspective. We haven’t failed anything. Truth is, bad things happen, we are entrusted to reduce the damages as much as possible without increasing the risks from another unprepared threat. We have saved many more lives because of the current “Codes” than unfortunate lives lost. Current codes have so much more built into them to help reduce “ALL” risk, not just the high profile risks that the media portrays as the biggest risk to a school. You state ” It would give the local rep the opportunity to be part of the solutions and gain back the trust of the public.” Why don’t we start with educating the public on why we have the codes that we do and enlighten them to all the risks that our schools deal with on a daily basis. There is no “One Solution Fits All.”

Roger, my perspective is not wrong, but perhaps you are not looking at the series of events that precipitated the development and use of the various blocking devices. The “codes” are not the problem, but they are certainly not being followed in all cases. I am not sure of the “we” you speak of, but our industry has failed in reacting early enough to hold of the development of these illegal items. Immediately after the Columbine tragedy (1999), there were calls to make schools and classrooms safer. Borne from the lack of clear solutions or direction from the ‘experts’ (and AHJ’s) in our industry, the general public came up with their own solutions. Educating the public, as you say, should have been done decades ago, and now we are crying foul for all of the blocking solutions being deployed. You are correct, there is not a single solution for every opening. It takes a comprehensive review of every school to evaluate the threats to life and properly and develop a plan for active shooters, life safety, fire control, etc. As I said, we are supposed to be the experts when is comes to these areas. Bad things do happen, but we have to be honest with ourselves too. Have we really done our best to mitigate these tragedies.

Hi Lori Green,

This article may need a little explanation in the beginning. I think that the article jumps into explaining a problem without helping readers to know the big picture of the problem and why it came to be an issue.

What if the article started with something like this:

School districts have responded to the threat of school shootings by adopting many different retrofit security devices, that seem to be less expensive or more secure than traditional locking hardware. These aftermarket products appear to offer a classroom barricade that stops school intruders, but these products also cause problems for more likely school issues such as life safety, fire protection and accessibility. The retrofit security devices may seem to be safer in a panic situation but many of these devices also block access by firefighters or paramedics, make exit difficult for children or people using wheelchairs or fail to meet the model safety code that guides local regulators.

All, as being both a parent, and also the installing technician, this article is very well read. But with this being said, I am both Nfpa 80 and 101 certified. We as an industry have not had a failure. Actually the opposite, her article is very correct, when we talk hardware, people are lost and don’t understand, they want a quick fix. I personally did a complete high school remodel here in Indiana, while we proceeded to do our work, staff of the school had lots and lots of questions. Like how does this work and will we be safe. I spent a very large amount of time with teachers and staff, as I changed both their doors and their hardware, explain how it works, and for how they where to use it, if the need ever arose.

After the remodel was complete, the school was shown how to have test drills, working with local enforcement, not only did it allow us to fix a few manufacturing issues, but it allowed the staff, the piece of mind that their system would work.

Knowledge is the power and the key, to success in any of these changes. Retrofits are unsafe and untested. The current industry hardware works, BUT, WE AS AN INDUSTRY HAVE TO MAKE TIME, SO THAT EVERYONE UNDERSTANDS HOW IT WORKS AND HOW TO MAKE IT WORK.

We owe it to the school, the kids and their parents. Great article Lori.

Hi All,

I respect your opinions and your dedication to safety.

I choose a secondary locking means, as you probably do when it comes to your personal safety.

I think we all have a deadbolt at home on our front and back door.

Temporary locking devices are only to be used as a last resort, once in a lifetime. I hope there is one available

if you or your children ever need one.

This picture (Link): http://www.nightlock.com/complianthardware shows clearly why thousands of schools, government facilities, and others, choose a Nightlock product as a secondary locking means as their backup plan.

The NFPA just added a second movement amendment for such events.

Times have changed, change is good.

.

Hi Joe –

I tried the link you included in your comment and received the error message “NOT FOUND, ERROR 404.” While it is true that NFPA 101-2018 now allows a second releasing operation, the motivation behind the amendment was to prevent the use of classroom barricade devices or “homemade” solutions. This is from the proponent’s substantiation for the TIA:

“Lacking the provision for two releasing operations on existing classroom doors, some schools are opting to purchase aftermarket barricade devices or utilize other ‘homemade’ solutions (e.g., sliding sections of fire hose over the door closer arm, rope, wedges, etc.), which restrict entry by a would-be assailant, but also restrict emergency egress and entry by school staff and emergency responders. Barricade devices can also be utilized by an assailant to contain occupants in a classroom and prevent assistance from entering.”

Although jurisdictions that have adopted the 2018 edition of NFPA 101 can now allow a separate releasing operation (like a deadbolt) on existing classroom doors in schools (not universities), the secondary lock must meet all of the requirements of the Life Safety Code. For example, the releasing hardware must be located between 34-48 inches above the floor, and the door must be able to be unlocked from the outside with a key or other credential. There is more information about the TIA here: https://idighardware.com/2019/08/nfpa-101-tia-1436/. Note that the International Building Code and International Fire Code do not allow 2 releasing operations to unlatch the door.

My primary focus is code-compliance and safety, and to that end I do not advise school districts to use separate deadbolts, surface bolts, or barricade devices. Locksets, which are already installed on most classroom doors, have proven effective in preventing unauthorized access, while allowing free egress for building occupants.

– Lori