This post will be published in Door Security + Safety

Have you ever been trapped? I have. I was doing a survey of the existing conditions in a very large old church in Boston. I entered a stairwell and when I reached the bottom of the stairs, the exterior door – well over 100 years old – would not open. The doors leading from the stairwell to each floor were locked. I was alone with no cell service, in a part of the building that might not have been occupied until Sunday. I eventually got the exterior door open, but it was a very scary experience.

Given the work that I have done for decades, trapping people in buildings is something I actively work to avoid; the model codes adopted across the U.S. are aligned on this as well. Throughout history, many tragedies have resulted from buildings where people were trapped by locked, blocked, or hidden doors. Because of these incidents, the model codes include several requirements to help prevent this from happening. With very few exceptions, doors must allow egress without a key, tool, special knowledge, or effort, and with no tight grasping, pinching, or twisting of the wrist. Locks must operate with one hand, and in most locations, one releasing motion must unlatch the door (all latches simultaneously). When these rules are followed, doors can be secured to prevent access, but will not trap occupants inside.

School Security

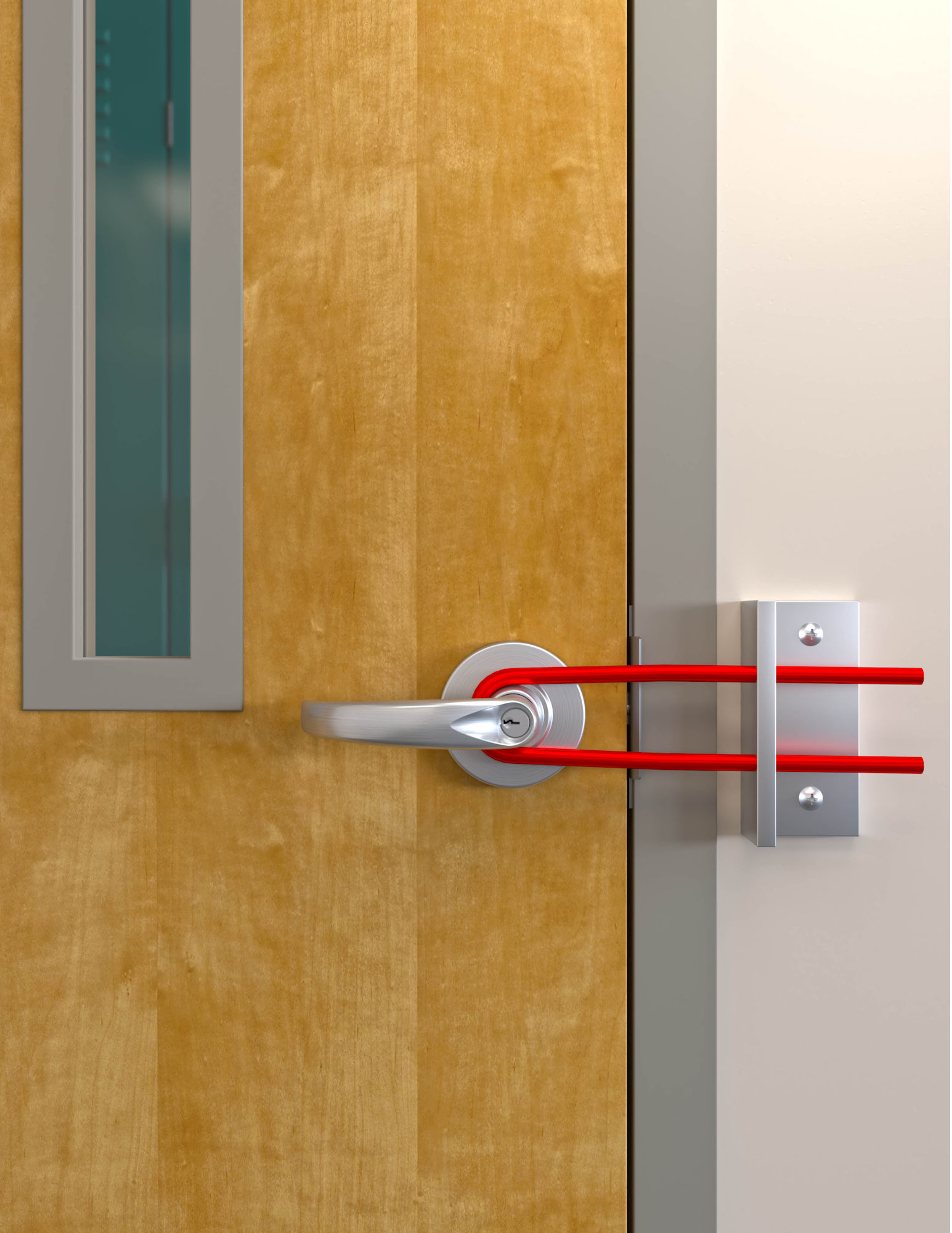

Securing a classroom door with a non-code-compliant classroom barricade device may deter egress as well as delaying or preventing authorized access.

These same mandates apply to classroom doors, along with a more recent code requirement for these doors to be able to be unlocked from the outside by someone with a key, credential, or other means approved by the code official. When evacuation is needed, exiting from a classroom must be intuitive and immediate. When someone inside the classroom needs help from school staff and/or emergency responders, authorized access from the outside must be readily achievable. Should students and teachers ever be trapped in a classroom? I think most people would agree that the answer is “no.” And if someone believes that “yes – students and teachers should be trapped in a classroom,” I’d love to hear their reasons.

As the fear of school shootings increased in recent years, there was a rush to secure the interior and exterior doors in school buildings. In some cases, these efforts have led to unfortunate choices that could trap students and teachers in their classrooms. Somewhere along the way, the need for locking the assailant OUT has led to the perception that others should be locked IN. Taking another look at school security will help to refocus on the balance of both life safety and security in schools.

The Partner Alliance for Safer Schools (PASS) recently published a document to help school administrators and other facility managers learn about the potential dangers associated with one type of retrofit security product – classroom barricade devices. The document is titled: Evidence-Based Safety and Security Decisions Regarding Classroom Barricade Devices, and it addresses three main topics: evacuation, emergency response, and accessibility.

Evacuation

Evacuating quickly and easily can be key to survival during an active shooter event, fire, or other type of emergency. Conversely, trapping building occupants can have tragic consequences. In several past school shootings, the shooter barricaded doors to delay emergency response. A recent article in Security Magazine referenced another incident that clearly illustrated the difference between doors that allowed egress and doors that did not:

In 2018, Dimitrios Pagourtzis killed 10 students and teachers and wounded 13 others at Santa Fe High School. According to one survivor’s account, the shooter went into two art classrooms and shot through windows on internal classroom doors and closets. In a documentary on the shooting, The Kids of Santa Fe: The Largest Unknown Mass Shooting, it was revealed that a back door of one of the art rooms was able to open, and approximately 20 people exited to safety. The other classroom’s back door didn’t open, costing lives in the tragedy because they couldn’t escape.

Another example: In January of 2022, a gunman entered the Congregation Beth Israel Synagogue in Colleyville, Texas. Four people were held hostage for more than 10 hours, and their escape demonstrates why it’s important to keep all options open – including the ability to exit – during this type of situation. From the Associated Press:

“Cohen said the men worked to keep the gunman engaged. They talked to the gunman, and he lectured them. At one point as the situation devolved, Cohen said the gunman told them to get on their knees. Cohen recalled rearing up in his chair and slowly moving his head and mouthing “no.” As the gunman moved to sit back down, Cohen said Cytron-Walker yelled to run.

“The exit wasn’t too far away,” Cytron-Walker said. “I told them to go. I threw a chair at the gunman, and I headed for the door. And all three of us were able to get out without even a shot being fired.”

Would the outcome of the synagogue situation have been different if the hostages were not able to exit freely – for example, if the intruder had barricaded the exit? I am reminded of the 2019 mosque shootings in Christchurch, New Zealand. The exit in one of the mosques had been secured with an electrified lock that did not allow free egress. Fifty people died in the shootings in Christchurch. How many could have survived if the exit door had allowed them to escape?

Emergency Response

The often-repeated argument for prioritizing security over life safety in schools is that no one has died in a school fire since 1958; that was the last school fire in the U.S. with a large loss of life (Our Lady of the Angels School, 92 children and 3 nuns died). Hearing this might lead people to believe that school fires are rare, but they are actually quite common. Fires will continue to occur in schools, but the strength of our model codes around egress and fire protection has greatly mitigated the consequences of these fires.

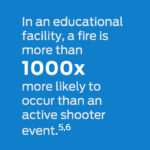

The PASS document states: In an educational facility, a fire is more than 1000x more likely to occur than an active shooter event. How can that be, when we are constantly seeing reports of school violence in the news and we rarely hear about fires in school buildings?

There are many sets of statistics on gun violence in schools, with different criteria for the types of events that are included. Some statistics include suicides, targeted shootings, accidental discharge of weapons, and gunfire in the parking lot, for example. A locked classroom door may not help during these types of incidents, but it could have a profound effect during an active shooter event. The FBI has published detailed data on active shooter events since 2000 and has reported a total of 38 active shooter events in educational buildings over the period from 2010 to 2020 – an average of 3.5 events per year.

So how many fires occur in educational buildings each year? Based on statistics from the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), during the period between 2010 and 2020, there were approximately 4,800 fires in schools and other educational occupancies each year. According to the FBI and NFPA figures, it is about 1,200 times more likely that a fire will occur in a particular school than an active shooter event. This demonstrates why it is important to consider fire protection, life safety, and egress in addition to security in schools.

There are other types of incidents where fast and efficient emergency response is needed. According to the National Center for Education Statistics Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety, students ages 12–18 experienced 764,600 criminal victimizations at school in 2019. If a student or teacher is being assaulted while trapped inside of a classroom, how long will it take for school staff or first responders to enter the room? There have already been incidents where an assailant purposely prevented access to a classroom, for example, at the STEM School Highlands Ranch, near Denver. One student was killed and 8 were injured – 2 students at the school have been charged with the crime. According to the arrest affidavit, during the shooting one of the assailants “pulled the magnetic strip on the door and pulled it shut so it couldn’t be opened from the outside.”

Seconds count in these situations, and if a school’s non-code-compliant security methods delay emergency response, there could be additional liability for the school district.

Accessibility

Code-compliant locksets used to secure classrooms help to ensure a balance of security, life safety, fire protection, and accessibility.

Another argument for ignoring the requirements of the codes and standards when focused on security is based on the idea that accessibility is not important during a school shooting. However, it is crucial for all building occupants to have access to and egress from a building, including people with physical disabilities.

The Guide for Developing High-Quality School Emergency Operations Plans is a joint publication of the U.S. Department of Education, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, and Federal Emergency Management Agency. This document states, “Plans must comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act, among other prohibitions on disability discrimination, across the spectrum of emergency management services, programs, and activities, including preparation, testing, notification and alerts, evacuation, transportation, sheltering, emergency medical care and services, transitioning back, recovery, and repairing and rebuilding.” Requirements for compliance with the ADA’s design standards are specifically referenced in the guide.

Conclusion

Most doors in schools are already lockable – securing them may just be a question of key distribution and/or staff training and drills. While planning to secure a school or other building, we must ensure that we’re not trading one problem for another. Doors can be locked securely with code-compliant door hardware to prevent unauthorized access without negatively impacting evacuation or emergency response. The hardware on these doors must be usable by all building occupants – including people with disabilities. And above all, security methods must not trap people inside of a building or room.

To download the referenced document from PASS as well as their school safety and security guidelines, a checklist, and other resources, visit their website at passk12.org.

You need to login or register to bookmark/favorite this content.

A masterwork of clarity on a complicated topic.

Your commitment to safety and security shines through.

I expect this will be one of your more popular and referenced columns.

Awww…thanks Tom! 🙂

– Lori

2 other points I always bring up is that not only do these devices slow emergency people responding but may could even be used by the assailants to do just that. The other point I always add is most of these devices have an adverse mental affect on the kids they say they want to protect.

Both good points, John!

– Lori

Well Done, as always, Lori.

Terrific references.

Not that you need another one, but one of my favorite trapped-in school references is still the Virginia Tech shootings. Bike locks that were purchased at a local hardware store were used by the shooter to lock Von Duprin 88 style exit devices together on the main 2 sets of doors.

Students could not leave, first responders could not get in. That led to a slow entry of first responders, and they got a lot us undeserved grief on this topic.

This is also one on the few cases where the shooter did the locking-in/trapping.

Yes, here is an article about the difficulty police had when trying to enter the building at Virginia Tech: https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/04/26/AR2007042602558.html. Two other examples where the intruder barricaded school doors to delay law enforcement are Platte Canyon High School (https://www.denverpost.com/2006/09/27/hostage-horror/), and West Nickel Mines Amish Schoolhouse (https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/08/23/AR2007082300243.html).

I’m sure we will see more of this in schools where the means of barricading the door is hanging on the wall. 🙁

– Lori