When discussing classroom locking, the requirements for accessibility are sometimes given a lower priority than the need for security. My next Decoded article explains why it is important for the ADA and all adopted codes and standards to be considered when choosing security products. Let me know if I missed anything!

This article will be published in the March 2020 issue of Door Security + Safety

.

In the last 5 years, many retrofit security products (also known as barricade devices) have entered the market, and have been considered for use in school districts, college and university campuses, and other types of buildings. While securing doors against unauthorized access is important, it’s crucial to make sure that the implemented security methods can not trap people inside of a room. This could occur if emergency egress is required after a secondary locking device is put in place, or if an unauthorized person installs a barricade device to purposely prevent others from leaving the room. In addition, many retrofit products do not comply with the model codes and accessibility standards and may violate the federal Americans With Disabilities Act.

In the last 5 years, many retrofit security products (also known as barricade devices) have entered the market, and have been considered for use in school districts, college and university campuses, and other types of buildings. While securing doors against unauthorized access is important, it’s crucial to make sure that the implemented security methods can not trap people inside of a room. This could occur if emergency egress is required after a secondary locking device is put in place, or if an unauthorized person installs a barricade device to purposely prevent others from leaving the room. In addition, many retrofit products do not comply with the model codes and accessibility standards and may violate the federal Americans With Disabilities Act.

Why comply?

The 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design are the currently-adopted accessibility standards enforceable by US law. A similar set of accessibility standards, called ICC A117.1 – Accessible and Usable Buildings and Facilities, is referenced by the International Building Code (IBC). States and local jurisdictions may have additional accessibility standards, and most states adopt building codes and fire codes to protect building occupants.

These codes and standards have been developed over time using a consensus process, which allows hundreds of stakeholders to work together to incorporate requirements that will provide the optimal level of safety. Most codes are modified every 3 years, in order to address new technologies as well as lessons learned in fires or other incidents and to avoid repeating past mistakes. All of these requirements help to ensure that buildings are safe and accessible for building occupants – including people with disabilities – by establishing design requirements for the construction and alteration of facilities.

The Guide for Developing High-Quality School Emergency Operations Plans is a joint publication of the U.S. Department of Education, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, and Federal Emergency Management Agency. This document states, “Plans must comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act, among other prohibitions on disability discrimination, across the spectrum of emergency management services, programs, and activities, including preparation, testing, notification and alerts, evacuation, transportation, sheltering, emergency medical care and services, transitioning back, recovery, and repairing and rebuilding.” Requirements for compliance with the ADA’s architectural requirements are specifically referenced in the guide.

With limited exceptions, state and local government facilities, public accommodations, and commercial facilities must meet the requirements of the ADA, but the requirement for accessibility extends beyond ADA enforcement. According to the International Building Code Commentary: “The fundamental philosophy of the code on the subject of accessibility is that everything is required to be accessible…In the early 1990s, building codes tended to describe where accessibility was required in each occupancy, and any circumstance not specifically identified was excluded. The more recent codes represent a fundamental change in approach. Now one must think of accessibility in terms of ‘if it is not specifically exempted, it must be accessible.’

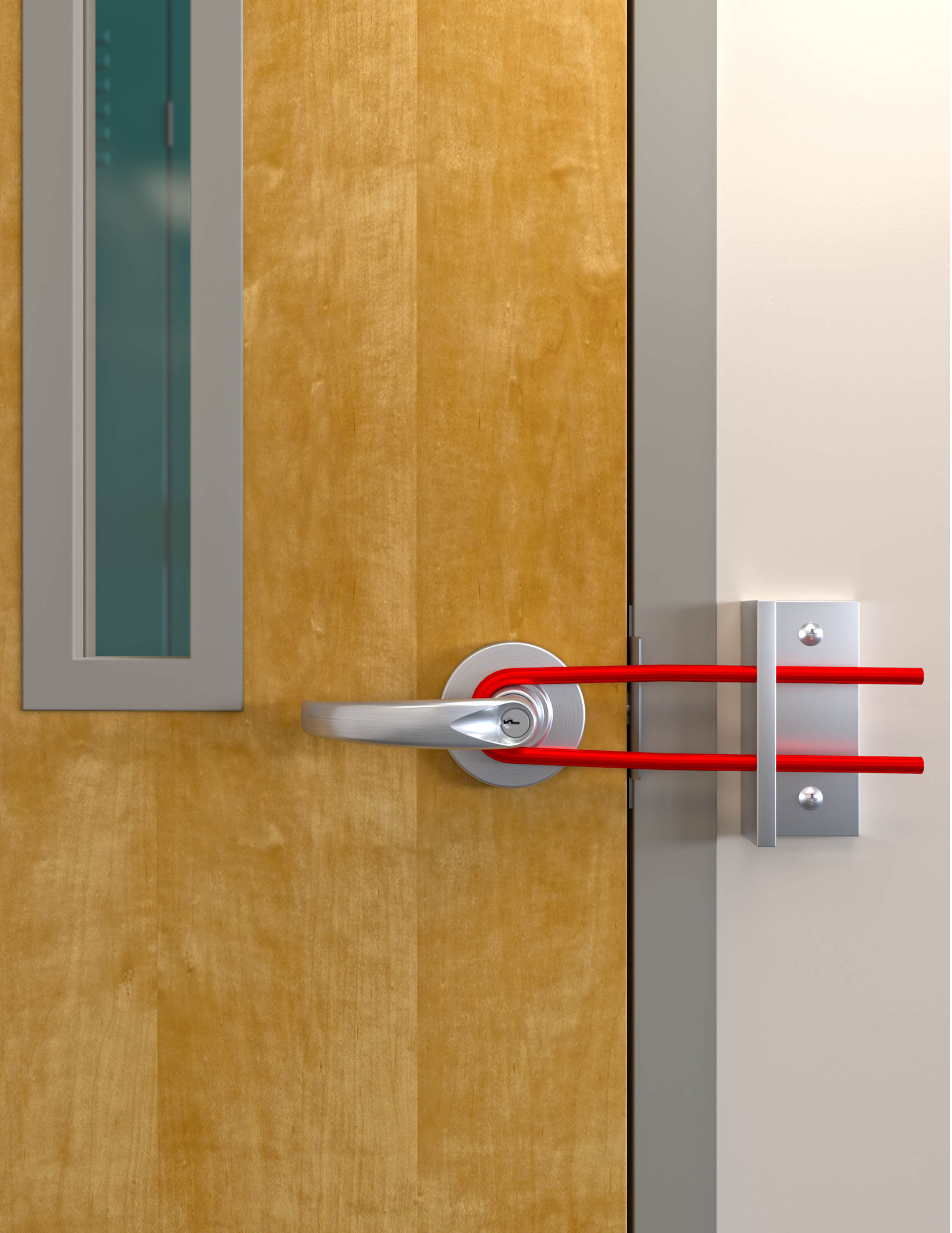

It could be said that accessibility and “egressibility” are equally important; the intent of the ADA is to ensure both. Some proponents of barricade devices have argued that locking hardware that is temporarily attached to the door is not required to comply with the ADA. While technically the ADA applies to hardware that is a permanent part of the assembly, a door with a temporary locking device that is not operable as required by the codes and standards can increase risk and liability. In order to comply with the accessibility standards, door hardware must meet some basic requirements so doors can be intuitively operated for both access and egress. The following examples of conceptual barricade devices illustrate some potential issues to watch out for.

Top of the Door

Some types of retrofit security devices are designed to be attached to the door closer arm, at the top of the door. Many news outlets have reported on school districts considering the use of short pieces of fire hose for this purpose.

Some types of retrofit security devices are designed to be attached to the door closer arm, at the top of the door. Many news outlets have reported on school districts considering the use of short pieces of fire hose for this purpose.

These methods can not be deployed or removed by someone who can not reach the top of the door, including people using wheelchairs, and children. The accessibility standards require releasing hardware to be installed between 34 inches and 48 inches above the floor so that it is within the reach range of most people.

When one university decided to employ the fire-hose method, facility personnel quickly realized that many doors to individual classrooms did not have door closers, so the pieces of fire hose could not be used. Another important consideration is that door closers were not designed as security devices – this method relies on the weakest link which is likely the screws attaching the door closer to the door or frame. Even in the best-case scenario, the fire hose will allow the door to open a few inches before the closer arm opens far enough to reach the limits of the sleeve. The fire hose/closer sleeve method of securing a door may give the illusion of security, but it is not an effective means of securing a door.

Secondary Locks

When an existing lockset can not be locked from the inside, adding a secondary locking device may seem more feasible than modifying the lockset. However, some retrofit security products do not comply with the accessibility requirement which states that hardware must be operable without tight grasping, pinching, or twisting of the wrist. Some users may not have the dexterity needed to operate the added security device. Many existing locksets can be retrofitted using conversion kits supplied by the lock manufacturer, to allow the door to be locked from the inside while still meeting the requirements of the codes and standards.

When an existing lockset can not be locked from the inside, adding a secondary locking device may seem more feasible than modifying the lockset. However, some retrofit security products do not comply with the accessibility requirement which states that hardware must be operable without tight grasping, pinching, or twisting of the wrist. Some users may not have the dexterity needed to operate the added security device. Many existing locksets can be retrofitted using conversion kits supplied by the lock manufacturer, to allow the door to be locked from the inside while still meeting the requirements of the codes and standards.

The force required to operate door hardware is addressed by the standards as well. The ADA Standards require hardware to be operable with 5 pounds of force, or less. ICC A117.1 limits operable force to 28 inch-pounds of rotational motion, or 15 pounds for hardware operated with a forward, pushing or pulling motion. In addition, the life safety codes require doors to be unlatched with one releasing operation, and without the use of a key, tool, special knowledge or effort. When installed on a door that has existing latching hardware, a secondary locking device is often in conflict with these requirements, and some may even require simultaneous two-handed operations.

Floor Level

Similar to the fire hose or sleeve on the closer arm, security devices that latch into the floor are outside of the allowable reach range defined by the accessibility standards. In addition, hardware projecting off the face of the door can create “catch-points” for a crutch, cane, or wheelchair footpad. The accessibility standards prohibit the installation of protruding hardware on the push side of the door, in the area at the bottom of the door measured 10 inches up from the floor.

Similar to the fire hose or sleeve on the closer arm, security devices that latch into the floor are outside of the allowable reach range defined by the accessibility standards. In addition, hardware projecting off the face of the door can create “catch-points” for a crutch, cane, or wheelchair footpad. The accessibility standards prohibit the installation of protruding hardware on the push side of the door, in the area at the bottom of the door measured 10 inches up from the floor.

In addition to the accessibility issues, there are several functional concerns with security devices that project into the floor. Holes in the floor could become filled with dirt or other material which prevents the device from securing the door. Brackets installed on the face of the door can be targets for abuse, as some facility managers have reported children standing on the bracket to “ride” the door as it swings. For any security device that is not permanently attached to the door, there is the question of how to store it so it is readily available in an emergency, but does not tempt someone to deploy it for mischievous or malicious purposes.

When any retrofit security products are installed on fire door assemblies, they can void the fire door label if they are not tested and listed for this purpose. The standard for fire doors also limits the modifications that can be made to an existing fire door. Most secondary locking devices have not been tested or certified in accordance with industry standards, so their performance can not be predicted.

DIY Security

Some facilities have implemented “homemade” security products to save money while attempting to augment security. Without compliance with regulations and product test standards, there is no guarantee that these devices will function as planned during an emergency. Will the device be removable after an intruder kicks the door a few times? Will someone with limited dexterity be able to remove the device? Will a person with vision impairment intuitively understand how the device is installed and removed?

Some facilities have implemented “homemade” security products to save money while attempting to augment security. Without compliance with regulations and product test standards, there is no guarantee that these devices will function as planned during an emergency. Will the device be removable after an intruder kicks the door a few times? Will someone with limited dexterity be able to remove the device? Will a person with vision impairment intuitively understand how the device is installed and removed?

Similar to the fire hose or closer sleeve, many of these devices rely on other components of the door assembly to perform in ways the hardware was never designed or tested to perform. For example, a retrofit security device that attaches to an existing lockset is dependent on the attachment of the inside lever handle to the lockset to provide security. This connection is not designed to withstand the force of an intruder trying to enter – that is not the inside lever’s function. A traditional lockset will deter unauthorized entry and will allow free and immediate egress, and locksets with lever handles can be operated as required by the accessibility standards.

In addition to the effects of vision impairments and orthopedic disabilities on the operation of doors, people with autism or other developmental differences need to anticipate familiar methods for egress. During a crisis, it’s even more critical that door operation does not require special knowledge or effort. There are dozens of barricade devices on the market, with many different methods of operation. Some of these products do not allow access from the outside or require a special tool to unlock the door. Delayed access for school staff and emergency responders could have serious consequences if an unauthorized person deploys a barricade device.

Bottom Line

A means of locking a door from the inside is crucial during an active-shooter event, but the security method used must be easily operable by all building occupants for egress. Traditional hardware is intuitive to operate and provides the optimal level of security. In past school shootings, locks have prevented shooters from entering classrooms, and studies of these shootings have not reported a locked door being breached through the lock. Most classroom doors are already equipped with locksets that will provide the necessary level of security.

Turning the lever handle of a lockset or pushing the touchpad to operate panic hardware allows immediate egress. No time is needed to consider how to open the door, and the vast majority of building occupants are able to operate standard commercial hardware. The ADA and other accessibility standards explain how to ensure that doors are operable easily and intuitively. When making security decisions, ignoring these standards increases risk and liability, and could negatively impact building occupants – including people with disabilities.

You need to login or register to bookmark/favorite this content.

Wow! fantastic read. I am always amazed at how much time is wasted on non compliant security devices when approved door hardware is most always available.

It amazes me too! I never would have guessed that people would start disregarding the codes – especially in schools! 🙁

– Lori

Very Good article and info. Thanks Lori. (The orange banner at the top has March 2019 as the date)

THANK YOU! It only took me 23 days to write the wrong year! 🙂

– Lori

The sad part is that the folks in educational facilities implementing these “solutions” fully intend to provide safety for their students, personnel and visitors but have limited understanding at best of the life safety codes. Additionally they have very limited budgets to introduce a solution. They are then given advice by someone who either has no knowledge of codes or worse ignore the codes in an opportunistic fashion.

Once given the low cost “solution” the natural tendency when a knowledgeable person presents the proper means is to focus on the cost and disregard the correct solution. I had a large district in NJ that was convinced to use the Fire Hose as illustrated above. When I advised the person of the issues, and proper means to achieve the goal he dismissed all options as too costly.

So is the goal saving money or providing safe facilities? Frankly I was astonished to find that a publication that focuses on School Safety was promoting these barrier devices.

Great article Lori.. as stated by Donnie . It truly does amaze me how much time goes into all these homemade devices. And that’s the point use them at home not in public places . However I would be reluctant to use them at home as well .lol . But I will admit some pretty novel ideas have been put forward.

Bravo Lori. Locks have been both protecting us and providing for our safety effectively for decades. I am unaware of any instances of active shooters breaching a locked door. I am also unaware of any instances where a barricade device has been deployed to thwart an active shooter. We are, however, aware of several instances where doors were barricaded by active shooters to act on their victims- Virginia Tech being the most deadly shooting in an educational facility in our history.

So will we make the work of modifying codes the responsibility of our politicians? Or will we listen to and respect the opinions of the experts on safety and security and the time tested process of developing our life safety codes?

There has to be a safety locking device for additional resistance that is ADA, NFPA and state building code compliant. I am on a mission to find one that does not violate any of these codes. Any information would be appreciated!!

Hi Nancy –

A traditional lock provides the necessary level of security, while also meeting the accessibility and egress requirements. Most classroom doors already have locks so it’s often just a matter of setting policies and following them.

– Lori