This article is published here with permission from Sheldon Wolfe of BWBR Architects and the Constructive Thoughts blog.

~~~

Tower of Babel

Come, let Us go down and there confuse their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech.

I recently enjoyed watching a video clip of a senate confirmation hearing, in which Scott Pruit, EPA Administrator nominee, was being grilled by Joni Ernst, Senator from Iowa (the fun starts at about 2:14). At issue was the term WOTUS, or “Waters of the United States.” Not knowing at the time I watched it what the term meant, it was amusing to see that 97 percent of Iowa would be governed by expansion of the existing definition. Further discussion focused on puddles and on a definition of a parking lot puddle as a “degraded wetland.”

The labyrinthine regulations of the federal government reminded me of regulations we in construction deal with every day. They are similarly complex and obscure, differing only in extent. I was not surprised that I didn’t understand the subjects of the senate hearing, but on further thought, I realized I really don’t know much about the countless codes and regulations that govern construction.

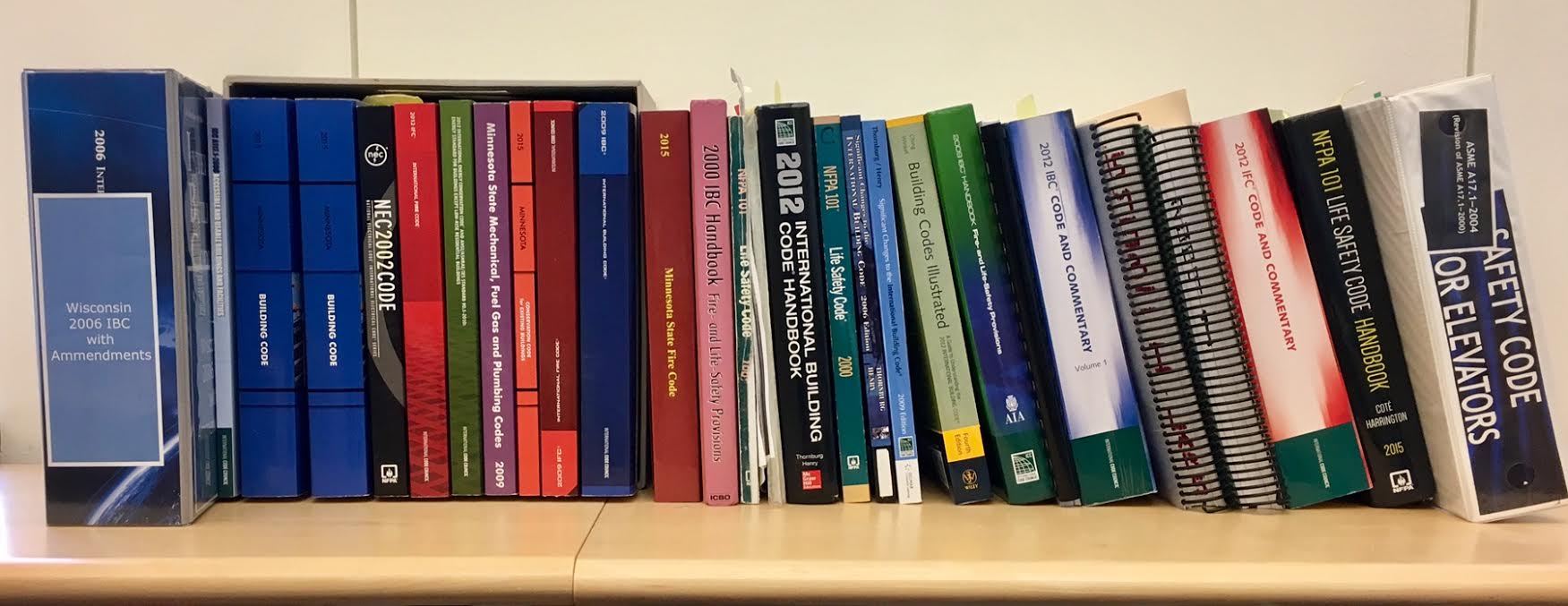

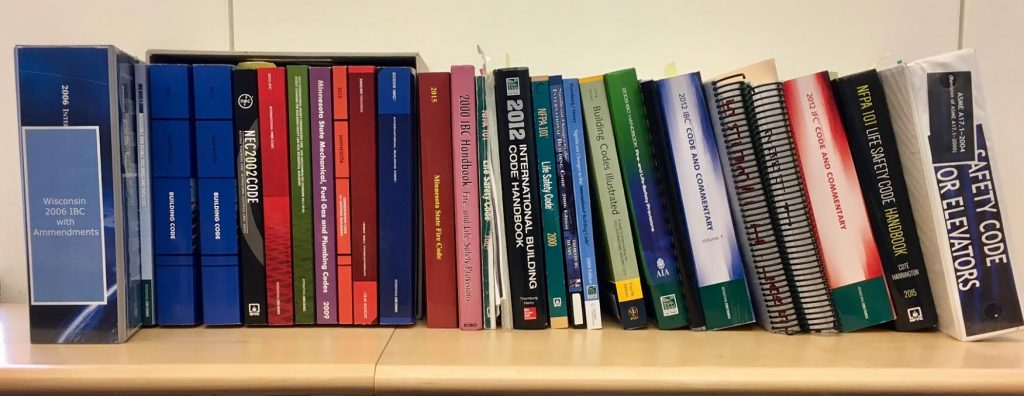

Nor, I’m sure, does anyone else. The picture that accompanies this article shows just a few of the code books we use at my office. In the picture are a few versions of the IBC, a couple of Wisconsin code binders, several books of Minnesota codes, a few versions of NFPA 101, an elevator code book, and a few books that explain what’s in the codes. This collection is nowhere near complete; we have many additional code books for Minnesota and Wisconsin, plus others for North Dakota, South Dakota, and Iowa, as well as for a couple of other states. I can only imagine what national and international firms have in their libraries.

Presumably, when someone certifies documents, that certification implies that the responsible person (or someone under that person’s direct supervision) understands everything in every statute, code, rule, and regulation governing the work of the project, and that the project complies with all of them. What does that tell us?

First, I think it’s safe to say that most of most regulations simply codify what was already common practice, much of which was based on empirical evidence. We build walls of 2 x 4s at 16 inches on center because it’s been done that way a long time and it seems to work. Later additions were added after due consideration; someone probably tested walls with framing at 24 inches on center and that worked, too.

Many requirements were added in response to building failures. Even then, I suspect much of what’s in the code is based on intuition, rather than on basic research beginning with the question, “What is required?” Though useful for comparative evaluations, code requirements often are not based on real-world applications. (See “Faith-based specifications.”)

I also think it’s safe to say it’s unlikely that any building complies with all regulations. Regardless of the source or value of those requirements, it’s clear that there are too many for any one person, or even several people, to understand. Making things more difficult is the fact that some information is restated in different codes, often in slightly different fashion, and some codes are more restrictive than others.

The International Code Council (ICC) publishes a dozen or so building and fire codes, which reference hundreds of standards published by ASHRAE, ASCE, and various other organizations, including about 50 of the 375 published by NFPA. These secondary codes also cite other standards, and so on, and so on, and so on. States then modify the basic codes, as do local jurisdictions. Some variations are required by local seismic and weather conditions, but many make little sense. All of these form the basic reference library for everyone involved in construction. Codes are continually being updated, usually on a three-year cycle. But not everyone is on the same cycle; some states update to follow the major codes more quickly than others, and different states will use different versions of the same codes.

My firm does mostly medical work, which must comply not only with the IBC and state codes, but also with NFPA 101, dictates of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Joint Commission, as well as requirements of individual clients. I’m sure we’re not alone, and that other types of construction have similar additional requirements.

Is all of this really necessary? I concede that there are special situations that require special treatment, but it’s hard to believe there are enough special circumstances to justify the mountain of code books we must deal with. While it is somewhat understandable that we have codes for specific conditions, there is no excuse for conflicts between different codes.

Several years ago, I was told that one part of one local code required an elevator room to have sprinklers, while part of another code prohibited sprinklers in elevator rooms. I have been told that that contradiction had been eliminated, but only after it had existed for many years.

A few years ago, one state had unique requirements for grab bars. Were there things about the residents of that state that prevented them from using the same grab bars used in other states? Some states have lower limits for VOCs than others. Do VOCs stop at state borders? If VOCs are hazardous, doesn’t it make sense to limit them everywhere?

If we want to fix construction, clear, consistent, non-conflicting codes would be a good start.

In a future article, we’ll look at a couple of examples of problems with code requirements and conflicts. If you have examples, please send them to me, or post them as a comment to this article

© 2017, Sheldon Wolfe, RA, FCSI, CCS, CCCA, CSC

Agree? Disagree? Leave your comments below, or at http://swconstructivethoughts.blogspot.com/

You need to login or register to bookmark/favorite this content.

Thank you Sheldon for telling it like it is.

Many can’t begin to grasp how many regs we have to deal with.

I have always found rules and regs to be most interesting, the result is a vast library dating back to pre – 1900.

Yes, the politicos also add many nonsense laws that require inclusion in our codes without their realizing the unintended consequences they may create.

“I can only imagine what national and international firms have in their libraries.”

Response : Consider using the free, online resources per the IBC (http://codes.iccsafe.org/index.html) and the NFPA (http://www.nfpa.org/codes-and-standards/all-codes-and-standards/list-of-codes-and-standards) … I’m sure the trees would appreciate it (although the code publishers may not).

“I think it’s safe to say that most of most regulations simply codify what was already common practice, much of which was based on empirical evidence.”

Response : Not necessary … there’s a saying that the codes should be written in red ink to signify all the lives lost before that code section was adopted. While the US can boast in having some of the safest buildings in the world, we nevertheless have over half a million structural fires every year resulting in thousands of deaths (http://www.nfpa.org/news-and-research/fire-statistics-and-reports/fire-statistics/fires-in-the-us/overall-fire-problem/structure-fires).

“Codes are continually being updated, usually on a three-year cycle.”

Response : Would we rather have the government (federal, state, and/or local) writing building codes instead of the (2) main code publishers, the ICC and the NFPA? While this does democratize code development by opening it up other stakeholders, the IBC and NFPA are in the business of selling code books. I would guess that the actual content changes in a typical 3-year cycle would equate to under 10% of the previous code edition. Some stakeholders actually want more frequent code cycles to reflect the ever-changing construction technologies.

“My firm does mostly medical work, which must comply not only with the IBC and state codes, but also with NFPA 101, dictates of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Joint Commission, as well as requirements of individual clients.”

Response : CMS adopted the 2012 NFPA Life Safety Code (LSC) on 07/05/16. Before that, health care facilities (HCF) had to meet the 2000 LSC from 03/11/03. HCFs, from a federal requirement, had the same code for over (13) years. You would think HCFs approved of this code “consistency” but a lot of them have been clamoring for the updated LSC ever since the 2003 edition came out.

“If we want to fix construction, clear, consistent, non-conflicting codes would be a good start.”

The ICC is the result of the National Building Code (NBC, or BOCA), the Uniform Building Code (UBC), and the Southern Building Code (SBC) combining. While some states and some local jurisdictions tweak the current ICC codes, the current situation is a lot more consistent than it was when multiple building codes were adopted across the country. While it would have been nice if NFPA had joined with the ICC (or vice-versa), having (2) main code developers may be better than having a single entity. Checks and balances?

Is code compliance difficult? Yes.

Does it complicate the design, construction, inspection, and occupancy phases? Yes.

Has it save countless lives and billions of dollars in property damage? Yes.

There is no doubt that codes do save lives and money. However, there is no justification for conflicting requirements or for the countless modifications imposed by local agencies that are not directly related to physical demands (seismic, elevation, weather, etc.).

Yes, there is more consistency now than in the good old days of UBC, BOCA, and SBC, but why not continue toward a single code? There is no reason to have multiple codes to address the same subjects. ICC and NFPA agree on most issues. Why force everyone to read and understand two or more separate codes that say mostly the same thing, then choose between conflicts?

Sheldon, I hope you read the responses to your article. I think it is spot on. I have to use 4 different codes State, County, ICC, UPC, and OSHA to come up with the minimum fixture requirements for anything except single family residential projects. Now if only specifiers adopted well defined accessibility standards and give access for the disabled its own place number in the specs like they did the faith based Green movement.

Again, does that make sense? If someone can justify having multiple codes, please do so!

I might not object to a large primary code that covered most things, with accessory codes for special subjects encountered only in some types of construction, but only if there were no redundancy, and only if the accessory codes were tightly coordinated with the primary code. That would eliminate the need to evaluate and compare multiple sources in most cases. Of course, it still would be possible to have conflicts between accessory codes, which leads us back to having one all-encompassing code.

In the last sentence, Jean refers to the way green design and accessibility requirements are addressed in MasterFormat. “Sustainable design” was assigned about a dozen section numbers, while accessible design requirements are not addressed.