This article is shared with the permission of Rick DeGroot, from the Facebook page: Building Construction for the Fire Service.

On March 6, 1982, an early morning fire in the Westchase Hilton Hotel in Houston, Texas, resulted in the death of 12 hotel guests and serious injury to three others. The fire, which was reported to the Houston Fire Department at 2:23 a.m., occurred in a guest room located on the fourth floor of the hotel’s 13-story high-rise tower. The fire involved mainly the contents of one guest room and exposed the fourth-floor corridor to severe heat and smoke conditions. Due to the building configuration, the fire was also able to extend horizontally to two adjoining rooms on the fourth floor. In addition, there was minor vertical exterior fire extension to three guest rooms on the fifth floor. Smoke was able to spread throughout the fire floor and, to varying degrees, to all levels of the building. Fire investigators later charged the hotel desk clerk and manager with repeatedly silencing the fire alarm and failure to immediately report the fire.

On March 6, 1982, an early morning fire in the Westchase Hilton Hotel in Houston, Texas, resulted in the death of 12 hotel guests and serious injury to three others. The fire, which was reported to the Houston Fire Department at 2:23 a.m., occurred in a guest room located on the fourth floor of the hotel’s 13-story high-rise tower. The fire involved mainly the contents of one guest room and exposed the fourth-floor corridor to severe heat and smoke conditions. Due to the building configuration, the fire was also able to extend horizontally to two adjoining rooms on the fourth floor. In addition, there was minor vertical exterior fire extension to three guest rooms on the fifth floor. Smoke was able to spread throughout the fire floor and, to varying degrees, to all levels of the building. Fire investigators later charged the hotel desk clerk and manager with repeatedly silencing the fire alarm and failure to immediately report the fire.

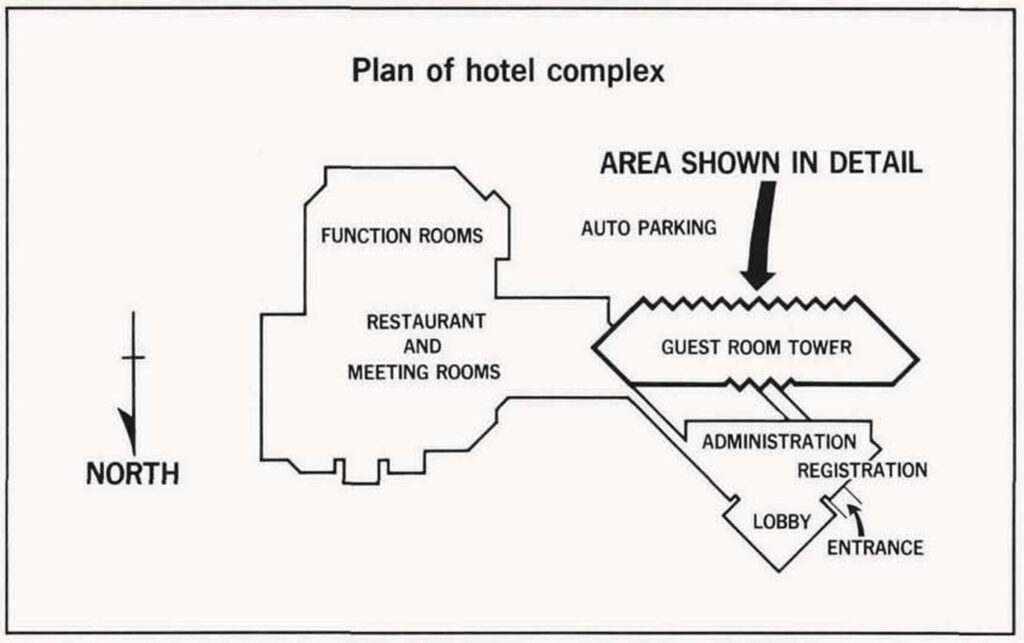

The Westchase Hilton Hotel, located at 9999 Westheimer Road about 15 miles west of downtown Houston, Texas, opened in late 1980. The hotel complex was built to the requirements of the City of Houston Building Code in existence when the building permit was issued in September 1979. The Certificate of Occupancy for the hotel was issued on November 24, 1980.

The hotel complex consisted of three separate areas of varying heights and construction. A one-story lobby building located to the north was of Type II Noncombustible construction with a sloping glass wall and roof facade. The building contained the lobby, registration area, and administrative office of the hotel. A one-story meeting and restaurant building to the east was also of Type II Noncombustible construction and contained a restaurant, lounge, kitchen, banquet and meeting rooms, and ancillary service areas.

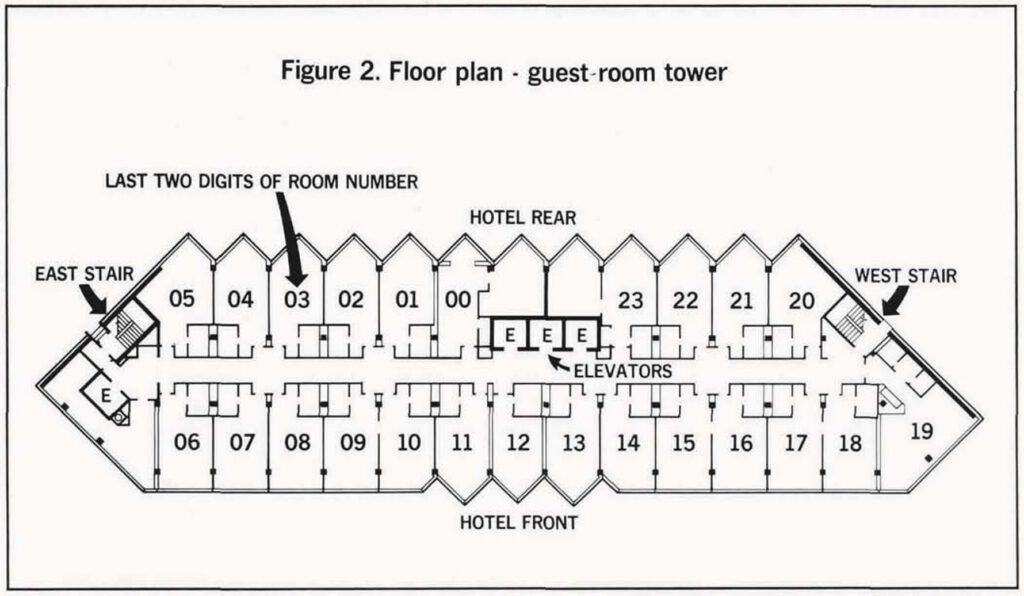

A 64-foot by 234-foot, 13-story high-rise tower contained 306 guest rooms, with a typical floor containing 24 rooms. The tower structure was of Type I Fire Resistive reinforced concrete construction. The exterior walls of the tower were of tempered glass in aluminum floor-to-ceiling frames. Aluminum plates were placed in the horizontal space between the exterior building skin and the reinforced concrete floor slabs. The void spaces between the aluminum plates, floor slabs, and exterior window lights were filled with mineral fiber thermal insulation.

Corridor and room partitions consisted of ½-inch gypsum wallboard on both sides of steel studs. Corridor walls had an additional layer of ½-inch gypsum wallboard on the corridor side of the wall to achieve a one-hour fire-resistive rating. Spaces between the studs were filled with cellulose insulation for sound attenuation.

Guest room corridor doors were 1 ¾-inch solid-core doors with a plastic laminate surface on steel frames. Doors were provided with two spring-hinge closers located at the top and bottom of the door. The latching mechanism provided positive latching of the door. In addition, the doors were equipped with dead-bolt locks. A ¼-inch by ½-inch sponge neoprene seal was provided on the door jambs to limit air infiltration.

Guest room corridor doors were 1 ¾-inch solid-core doors with a plastic laminate surface on steel frames. Doors were provided with two spring-hinge closers located at the top and bottom of the door. The latching mechanism provided positive latching of the door. In addition, the doors were equipped with dead-bolt locks. A ¼-inch by ½-inch sponge neoprene seal was provided on the door jambs to limit air infiltration.

Wall finish for guest rooms was a vinyl wall covering consisting mainly polyvinylchloride with loose fibers of cotton, rayon, and a trace of polyester bonded on the back. An adhesive was used to attach the wall covering to the gypsum wallboard. The ceiling finish in the guest rooms and exit access corridors consisted of textured stucco finish applied directly to the underside of the reinforced concrete floor slabs. The concrete slab, floor, and ceiling assemblies for the high-rise were determined to have a two-hour fire-resistive rating.

Guest room carpeting consisted of short, cut-loop nylon pile with a polyurethane padding bonded to a secondary backing of jute fibers. Room draperies were of woven cotton fabrics. The lining attached to the draperies was a polyester-cotton blend faced with vinyl polymer coating. The sheer drapery was a polyester fabric. In the guest room tower, corridor walls were covered with vinyl wall coverings, and the corridor floors were carpeted.

Exits for the guest room floors were provided by enclosed stairways located at the ends of the 182-foot central corridor. The stairways were designed to have a two-hour fire-resistive rating, as were the vertical shafts. The east stairway, closest to the room of fire origin, was a smokeproof tower with a pressurized stairway. The west stairway was not pressurized. Both stairways discharged directly to the exterior of the building. Each doorway to the stairways was provided with one 1 ½-hour, B-labeled door with self-closing device. Exit stairway locations were indicated by illuminated directional exit signs placed at the junction of the corridor and a small foyer. Within this small foyer area were exit stairway and storage room doors, similar in appearance, but lacking additional markings to distinguish the exit.

The smokeproof stairway was by means of a roof-mounted fan unit. The vestibule between the guest room tower corridor and the stairway was provided with an additional supply of outside air by fan and air was removed by an exhaust fan. Stairway pressurization and vestibule supply and exhaust fans were by operation of the fire alarm system.

The HVAC system for the guest room tower included individually controlled fan-coil units located in each guest room in an area above bathroom suspended ceilings. The units were supplied with outside make-up air through ducts located in common bathrooms walls between adjacent guest rooms. The supply ducts terminated in a plenum area located behind the fan-coil units. Return air from the guest rooms passed through grills to the fan-coil units.

The furnishings in Room 404, the room of fire origin, were typical of the furnishings of rooms in the hotel’s residential tower. Room 404 and similarly arranged rooms included two double beds with spring mattresses and box springs, wall-mounted headboards, two upholstered chairs, a small round table, a nightstand, a large upright cabinet containing a television, and a wall-mounted desk/dresser assembly with chair.

The hotel was provided with a fire alarm system that had a presignal feature and was not directly connected to the fire department or a central station. In the residential tower, the system was arranged with three manual pull stations on each floor near the stairways and elevator lobby. Horn/strobe light alarm alerting devices were near the pull stations. Activation of either a manual pull station or a corridor smoke detector produced an alarm at the annunciator panel with a visual zone display located at the registration desk. The presignal feature for the alarm system was set for three minutes to allow time for the investigation of the alarm source. At the end of the three-minute presignal cycle, the system was designed to sound an evacuation alarm on the floor of activation and the floors above and below. A key-operated switch that was provided at the annunciator panel could sound a general evacuation alarm for the entire building. The alarm system was also designed to shut down the corridor HVAC system, return elevators to the first-floor lobby area, and activate the east stairway pressurization and vestibule exhaust systems.

A single smoke detector connected to the fire alarm was located in the exit-access corridor on each floor near the elevators. Each guest room was provided with a single-station battery-operated smoke detector that was not connected to the fire alarm system. The smoke detectors were placed in the guest rooms after the hotel was in operation to comply with a Houston ordinance requiring a smoke detector in each residential unit subject to rental.

The guest room tower was equipped with a standpipe system with valve connections at the floor landings in each exit stairway. In addition, hose cabinets with 1 ½-inch hose lines for occupant use were provided at each end of the corridor near the exit stairway doors. The standpipe system was provided with a 750-gpm fire pump and a 2,500-gallon reserve water supply.

The building was not fully protected by automatic sprinklers; however, partial sprinkler protection was installed in linen chutes. The sprinklers were located on alternate odd-numbered floors. A waterflow alarm device connected to the fire alarm system was provided on the sprinkler supply piping from the standpipe riser.

The hotel fire safety plan designated hotel staff members to specific fire emergency functions and outlined actions to be taken by each staff member during a fire emergency. The plan designated staff members to investigate a source of an alarm, form evacuation teams, notify guests, determine evacuation routes, and form the fire brigade. The plan also specified actions to be taken by front desk personnel and the hotel operator. The Houston Fire Department had a prefire plan for the hotel, using as a basis their standard high-rise building prefire plan.

The hotel fire safety plan designated hotel staff members to specific fire emergency functions and outlined actions to be taken by each staff member during a fire emergency. The plan designated staff members to investigate a source of an alarm, form evacuation teams, notify guests, determine evacuation routes, and form the fire brigade. The plan also specified actions to be taken by front desk personnel and the hotel operator. The Houston Fire Department had a prefire plan for the hotel, using as a basis their standard high-rise building prefire plan.

Area weather at the time of the fire included a temperature of 48 degrees F and relative humidity of 68% with a north wind at 21 mph under cloudy skies (Weather Underground). Note: Research by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has shown wind speeds on the order of 10 to 20 mph are sufficient to create wind-driven fire conditions in a structure with an uncontrolled flow path (Madrzykowski and Kerber 2009). The NFPA report makes no mention of the effect of the weather on the outcome of the incident.

At the time of the fire, approximately 200 guests occupied some 150 of the 306 rooms in the hotel. Many of the occupants were members of one family and family friends staying at the hotel to attend a wedding on Saturday morning. Most occupants were asleep in their rooms, however, several guests were entering the hotel to check in after night travel or were returning to the hotel following the 2:00 a.m. closing of restaurants, lounges, and clubs in the Houston area.

One of the first notifications of the fire to the hotel staff was made at approximately 2:10 a.m. by an eighth-floor guest who discovered smoke in her room which was the first occupied room directly above the room of fire origin on the fourth floor and telephoned the front desk. At about the same time, an alarm signal from the single eighth-floor corridor smoke detector was received at the annunciator panel located at the front desk. A security guard soon arrived to investigate the reported smoke condition in Room 804.

The occupant of Room 804 packed her belongings and left her room after asking the security guard if they should alert the other guests. The security guard replied, “No, not yet.” The guard then reentered the corridor to search for the source of the smoke. The guest then telephoned the front desk from a house phone located in the corridor and asked the operator, “Shouldn’t the operator be informing the other guests?” The guest was reportedly told, “No, wait until the fire department gets here.” The guest then attempted to leave the floor via the passenger elevators but found that they were inoperative, so she used the stairway to evacuate the building.

The first person known to have discovered the fire on the fourth floor was one of the male occupants of Room 404, who was returning to the hotel with his date. Entering the hotel at approximately 2:20 a.m., they found the passenger elevator doors in the open position, but the elevators would not respond to their activation of the floor buttons. Familiar with the building, the couple walked to the east end of the corridor and took the service elevator to the fourth floor. As the doors opened, the couple observed a haze of smoke in the corridor.

The occupant used his key to unlock the door to Room 404 and found the room filled with smoke and observed a fire in the vicinity of the bed closest to the window. He entered the room in an attempt to extinguish the fire with a pillow. His date returned to the first floor via the service elevator to notify the hotel staff of the fire. Unable to control the fire, the occupant located his semiconscious roommate on the floor at the end of the bed closest to the corridor door and pulled him into the corridor. He assisted his roommate to the west stairway and returned to the room to search for his roommate’s date. He did not know that his roommate’s date had left earlier. Unable to locate his roommate’s date in the room, which by this time was heavily charged with smoke and heat, the guest returned to the west stairway to assist his roommate from the building. After the occupant left the room, the guest room door apparently remained in a partially open position. Both occupants escaped safely from the building.

Houston Fire Station 69, the closest first-alarm fire company, was located 1 ½ road miles from the hotel. At 2:23:13 a.m., the fire department dispatcher received a call from the hotel desk clerk reporting a fire of unknown type. After some discussion with the desk clerk, a first-alarm assignment was dispatched at 2:27:38 a.m.

Firefighters arrived at 2:31 a.m. and the fire was quickly contained to the room of origin and a portion of the corridor in the immediate area of the room of origin by responding firefighters. Because of the sawtooth configuration of the exterior wall, the fire was also able to extend horizontally to expose Rooms 403 and 405, which were adjacent to the room of origin. The fire was also able to extend vertically (auto-exposure) through the exterior windows broken by the intense heat to a fifth-floor guest room directly above the room of origin. However, fire damage to these rooms was relatively minor.

There was severe damage in the room of origin, with almost total consumption of bedding materials, wall and floor coverings, and room furniture. Although there was damage along the entire length of the fourth-floor exit access corridor, most of the damage was confined to a segment of corridor wall and floor coverings in the immediate vicinity of the room of origin. There was no structural damage to the building.

All the fatalities were occupants of the fire floor. A family of four and a family of five were found in Rooms 407 and 411. Guest rooms doors to both rooms were found closed. The occupant of Room 402 was found dead in the corridor outside Room 413. In addition, five occupants on the fire floor were hospitalized: four in critical condition, and one in serious condition. Two of the injured died soon after the fire. Firefighters found the injured behind closed doors in guest rooms and in the fourth-floor exit access corridor.

The victims ranged in age from 2 to 67 years old, seven females and five males. All of the victims died from smoke inhalation. Investigators could not determine conclusively whether any of the victims found in their rooms had opened their guest room doors or attempted to escape into the corridor, however, the bodies of the four victims in Room 411 were found clustered at the entry door. Of the total of 30 fourth-floor occupants at the time of the fire, 13 survivors were rescued by the fire department: eight by aerial ladder, three from guest rooms through the corridor and down the stairways, and two from the corridor and down the stairways.

As determined by fire investigators, the probable cause for the fire was an accidental cigarette ignition of an upholstered chair located near the window wall in 404. The fire then spread to the combustible furnishings in the room until reaching full room involvement. Some and heat then entered the fourth-floor corridor through the partially open door, leading to rapid deterioration of conditions in the corridor. Flames directly impinged on the doors of Room 407 and 408, directly across the corridor from Room 404. Flame spread in the corridor was limited to the vicinity of the room of origin however, smoke conditions were evident the entire length of the corridor. Fourth-floor survivors indicated that smoke conditions were so intense that they had to feel their way along the corridor walls to reach an exit.

Once smoke entered the fourth-floor corridor, the primary avenues of smoke spread to the upper floors included elevator shafts and the corridor HVAC system. Sometime before the arrival of the fire department, the door to the fourth-floor west stairway reportedly had been propped open with a chair. This allowed smoke to penetrate the stairway and to migrate vertically to the upper floors and prevented the use of this stairway as a means of escape for some occupants on the upper floors.

Prior to the arrival of fire units, the intense heat in the room of origin broke out the window glass on the south wall and fire vented, allowing flame, heat, and smoke to extend up the exterior of the south facade of the tower, exposing and causing minor damage to Room 504. This venting process, however, reduced the amount of smoke and heat entering the interior spaces of the building.

At the time of the fire, nearly 200 guests were registered at the hotel. On the fourth-floor, 15 of the 24 rooms were occupied by 30 guests. Some of the surviving occupants were awakened by running, yelling, or loud noises of the guests in the fourth-floor corridor or in other rooms. A few fourth-floor occupants who became aware of the fire early in the incident were able to exit from their rooms to the stairways and escape. Some were found overcome by smoke in the corridor by firefighters. The majority who became aware of the fire later found that smoke and heat conditions in the corridor precluded their escape and were trapped in their rooms. These occupants were either overcome by smoke or were rescued over ladders and removed from their rooms by fire personnel. Some occupants took actions within their rooms for survival by placing wet towels around the doorway and alerting the fire department of their presence via telephone while they awaited rescue. Several occupants on the fourth and other floors attempted to break the tempered glass windows with varying degrees of success.

Summary from the NFPA report:

The fire at the Westchase Hilton, like other recent severe hotel fires, was in a modern, recently completed fire-resistive structure with a number of built-in fire protection features. Yet 12 out of 30 occupants of the fire floor were fatalities. The successful interior and exterior rescues of 13 occupants from the fire floor by fire personnel are considered to have been significant in reducing the possible number of fatalities and/or injuries. The severe heat and smoke exposure to the fire floor resulted after a combination of events and factors that allowed the room of origin in this nonsprinklered building to reach full fire involvement.

Contributing Factors:

- Lack of detection and extinguishment of the fire in the incipient stage. A severe threat to life safety resulted from the guest room fire that involved combustible contents in this unsprinklered hotel. The life safety record in such facilities protected by a complete automatic sprinkler system is excellent. An automatic sprinkler system could have extinguished the fire and also provided an alarm for notification of hotel management and guests. Automatic notification of the fire department would have allowed the fire department to respond to the hotel to assist guests and hotel management.

- The guest room door of the room of origin did not close completely, contributing to the severe heat and smoke exposure to the fourth-floor corridor and other guest rooms. The door, although equipped with self-closing hardware, did not close completely. This condition increased the severity of heat and smoke exposure in the corridor, and greatly reduced the chances of survival on the fire floor. Smoke also spread from the fourth floor to other floors through elevator shafts and the corridor HVAC system. The door installation and maintenance details were not available to the investigators. It appears that the carpet may have interfered with the door swing. A closed door throughout the fire could have reduced or delayed heat and smoke spread to the corridor.

- The lack of an evacuation alarm in the early stages of the fire to alert guests on the fire floor. Proper staff action was essential in order to continue the emergency procedures that should have been initiated following notification and the automatic activation of the fire alarm system. This did not occur and resulted in evacuation alarms not sounding or being heard. Fourth-floor guests became aware of the fire by other means, and only a few were able to successfully evacuate the building on their own. Those who were forced to remain in their rooms because of severe corridor conditions faced a serious threat to their safety. The initial notification from the eighth floor caused by smoke migration may have diverted attention from the fire floor, delaying discovery and alerting of fourth-floor guests. There was insufficient data to determine the effect of possible fire alarm system impairments or malfunction on the evacuation alarm performance during the fire.

During the investigation of the fire, it was discovered that the hotel desk had repeated silenced the zone alarm for the fourth floor before realizing that there was an actual fire. Fire officials stated that desk clerk James Harvey, who had not been briefed on the alarm system, aborted the alarm several times over a period of several minutes because he did not know what the buzzer ringing on the switchboard was. The cutoff caused the alarm to reset and after three minutes it went off again. Harvey said that he cut off the alarm the second time and possibly a third time before he realized there was a fire. The clerk did not know that silencing the buzzer at the switchboard also silenced the alarm on the fourth floor. This action seriously delayed discovery, notification and response to the emergency by the occupants, hotel staff and the fire department for a period of about ten minutes.

The desk clerk and the hotel manager faced misdemeanor charges stemming from fire code violations including the silencing of the fire alarm and failure to immediately report the fire to the fire department. The charges were later dropped by the prosecutor.

Fire protection systems in modern high-rise occupancies are dependent upon three major components to successfully protect the occupants during a fire in the building. First, a properly designed, installed and maintained full coverage automatic fire sprinkler system must be present. Second, construction features such as self-closing doors, fire dampers in ventilation equipment, and internal fire separation walls that are designed to isolate fire, heat and smoke during a fire in a structure must be properly designed, installed and maintained. And third, a properly designed, installed and maintained automatic fire alarm system that simultaneously alerts occupants, building staff and the fire department must be present. If any of these three “legs of the stool” are missing or malfunctioning, the lives of the occupants, hotel staff and responding firefighters are put at risk.

Following this incident and other high-profile, high loss of life hotel fires in North America in the 19th and 20th centuries, public awareness of the fire safety deficiencies of many hotels, theaters, places of public assembly, and high-rise buildings was brought to light. Effective change in the codes to address these shortcomings came only after multiple tragedies took the lives of many victims and caused injuries to hundreds. Many of the fire safety design features that we recognize today in these types of occupancies are a direct result of the lessons learned from these incidents. However, it was not until congressional passage of the Hotel and Motel Fire Safety Act of 1990 that required hard-wired, single-station smoke detectors to be installed in each guest room and an automatic sprinkler system to be installed in all accommodations used by federal employees for overnight stays, conventions, meetings, and training events except in places that are three stories or lower, did the hospitality industry begin to update the fire safety features in their properties rather than risk the loss of lucrative federal business.

We have attached photos and floor plans from the incident. Thanks to group member Karl K Thompson for providing a copy of the NFPA report on the incident.

We have also attached a recent article published in Fire Engineering magazine by Brian Butler on hotel and motel fire operations: https://www.fireengineering.com/…/fighting-fires-in…/

Thanks to multiple media sources for additional information for this article.

Remember the lives lost during this incident by visiting a hotel, motel, boarding house, dormitory or other transient lodging facility in your local response district and reviewing the fire protection features of the occupancy and the emergency operations plan with your crew members today.

Get Out There And Know Your Local!!!