In Mark Kuhn’s next post, he shares his deep thoughts on the topic of electric strikes. We’d love to hear your opinions on the matter…feel free to leave a comment!

~~~

I just arriveed home from a week of teaching at the Spring DHI school – I love teaching the next generation of door and hardware professionals. If you sit down with me and we talk about work for any amount of time at this point in my career (41 years) you will hear me use the word “Legacy.” It really is on my mind a lot.

When I teach at DHI school I love to teach the core classes offered. Whether it’s a class on estimating a project, learning codes and standards, or the class I taught last week – “Door, Frame and Hardware Applications” – this basically covers every aspect of the commercial door and hardware industry. Teaching these classes give folks a solid foundation on which to build a great career and I want to be a part of that!

So I came back from teaching and decided to tackle a post that I’ve had on my “to do” list for a while, but have been putting it off because I’m sure it will be a little controversial.

Now that I’ve got your attention – LOL! – I would like to talk about the electric strike.

Now that I’ve got your attention – LOL! – I would like to talk about the electric strike.

Just about every week as a specwriter I need to convince a building owner or architect that electrified locks and electrified panic hardware are a far better choice than an electric strike. And I will admit that even though I feel I have a strong argument, the loyalty to the electric strike is far stronger in some cases.

Before I start, here’s a little history lesson. The electric strike was developed in 1886 by D. Rousseau and patented as an “electric door opener.” The purpose was to remotely release apartment entrance doors. SHOCKED?! I WAS! For those of you who are curious, according to Google, homes only started getting electricity in 1878 and nearly 50 years later, in 1925, only half of American homes had power. So, when I tell folks that the electric strike is “old technology” (and this is usually my first debate point), I’m not wrong.

Debate Point #2: When compared to an electric lock or electrified panic hardware, electric strikes can be a little “sloppy.” Since an electric strike needs to work with hardware from many different manufacturers, the tolerances are not as exact as the strike that is made for a specific lock or panic. The oversized tolerances (leading to the potential sloppiness) can be especially true when used with a mortise lockset. This is because the strike and mortise lock center line dimension are typically a standard dimension based on the door/frame manufacturer and the latchbolt location varies between lock manufacturers. This varying latchbolt location requires the use of either a variety of face plates or filler plates to be used on the electric strike.

Point #3: Most models of electric strikes will not release reliably under sideload pressure. If anyone has ever experienced the need to pull a door to relieve the pressure before pushing the door to open it, you know what I mean. Sometimes this can be the result of HVAC imbalance or a misaligned door frame, and sometimes it can be as simple as seals or silencers creating the pressure, but either way this can be an issue.

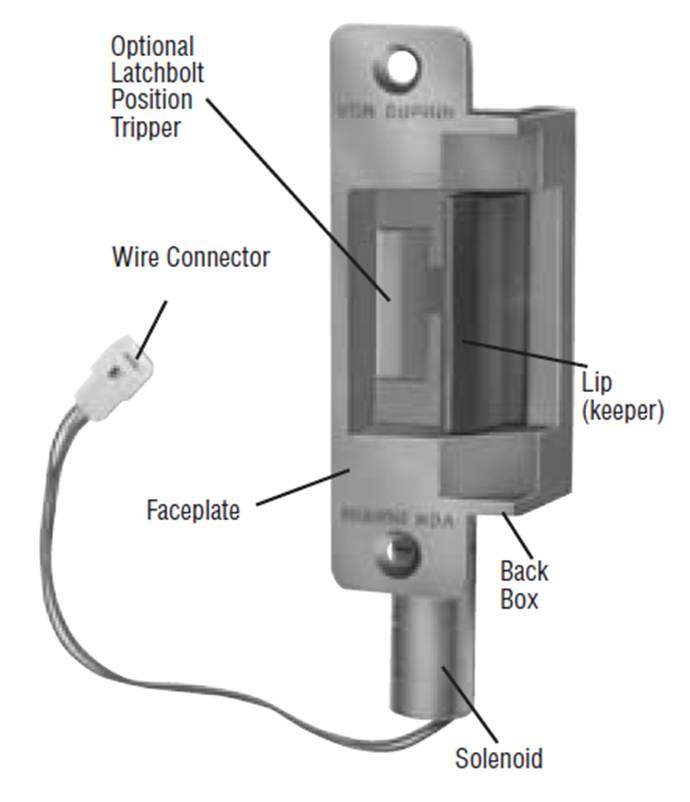

Cuatro: Electric strikes include solenoids which use more power and produce more heat, while most electric locks and panics are motor driven, using less electricity and running cool.

And last but certainly not least, in most cases the electric strike only performs one duty – it merely releases the door. This poses a problem for a lot of access control systems. On most electrified openings today, we are doing more than just opening the door – we are also monitoring the door. If I use an electric strike and I also want to monitor the door, I have to use a separate “request to exit switch” (normally in the form of a passive infrared detector) along with a door position switch. These three components require three conduit runs and three work boxes, etc. If I use an electric lock, I can accomplish all with one piece of hardware.

Now that I’m done with the functionality part of my debate, Let’s talk about codes!

Now that I’m done with the functionality part of my debate, Let’s talk about codes!

Probably the most import reason I specify electric locks and panics instead of electric strikes is because in some applications, I must. Lori has done a great job in a past blog post of covering this subject so I’m just going to hit some highlights.

If you have a fire rated opening, then you must have “positive latching” hardware. Positive latching is a term that all of us hardware people throw around pretty loosely but what it means is…when the door is closed, the latch bolt must be engage in the strike so that in case of a fire the door does not open.

Here’s the problem with electric strikes…The only way they can be used on a fire rated door is if they are fail secure. If a fail safe strike is installed on a fire rated door it DOES NOT meet the positive latching requirement. The main place this comes up is at stairwell reentry locations.

I feel that before I wrap up this post, I should talk about the reasons we WILL specify an electric (besides when requested by the owner). The main place we have specified electric strikes is where we are using an auto operator. To use an automatic operator to open a door, we must first unlatch the door. This is where the electric strike works best, because it allows the operator to open the door without interference from the latch bolt. But there is an exciting new product coming your way that will even replace the electric strike at these locations as well…stay tuned!

So….have I convinced you that electrified panic hardware or electrified lockset is a better choice than the electric strike? I’d love to hear your thoughts!

You need to login or register to bookmark/favorite this content.

I’d love to see more from the security side about why strikes are not as good as they seem, because the alternative (maglocs) that seems to be favored by folks who come at this world from the “brains” side (vs door/hardware) has even more problems than a strike from a life-safety standpoint.

Furthermore, I think one of the biggest reasons we don’t see more uptake of electrified hardware (aside from higher cost, of course) is the issues involved with power transfer and door coring. While there have been some options put on the market for wireless power transfer from frame to door over the past years (Securitron, SDC, and a few noname vendors make products for this), these have severe limitations in terms of power output (250-300mA @ 24V) and duration (90s max at full power, most likely due to thermal limits) that make them difficult to use for applications where doors have to be held unlocked for public operation and not usable in MLR or ELR situations.

Latchside contacts (Securitech Yamaka) are also an option, but are difficult to use for some applications (like transferring a supervised REX switch to an access control system) without tricky EOL handling, and you need multiple sets to transfer power, REX, and possibly lockset-side latchbolt monitoring (as latchbolt monitoring in the strike can’t tell the difference between normal latchbolt retraction and the door being ripped from its frame by a forced entry) from frame to door.

This leaves frame-actuator-controlled or integrated-power-transfer mortise locks as the last sane option if you don’t want to butcher your door with a core-drilling jig or live with electric strike issues. Sadly, SDC discontinued the fail-secure versions of the HiTower around COVID-time, which leaves ACSI as the only maker of frame-actuator-controlled fail-secure mortise locks, and the Inox PD97PT, while a freaking awesome concept, is only intended for sliding (vs swing) doors. (It’s also fail-_neutral_, vs. being fail-safe or fail-secure, which makes it a unicorn in that aspect as well.)

So, as far as I’m concerned, anyone who came up with an integrated-power-transfer electrified mortise lock for swinging doors that supported continuous energization at a minimum, if not the ability to transfer REX through the door to frame interface, would be a major breath of fresh air in this tired world. Either that, or I’d love it if DormaKaba extended their PowerPlex energy harvesting tech to the smart mortise lock world, as that’d lop a lot of low-end apps off from strikes right there (currently, the PowerPlex 2000 codelock has it, but is only available in the form of panic trim.)

Or am I missing something here? Inquiring minds want to know…(and would also like the fail-secure HiTower to come back!)

I agree and stay tuned for a future post where I speak to the overuse (and many times misuse) of maglocks. But as far as cost is concerned, believe it or not even excluding labor (extra conduit runs) it’s cheaper to use an electronic lockset with RX and DPS built in than it is to supply all the individual items (E-STK, PIR & DPS). As far as some of the other products that you’ve mentioned, I just don’t see them utilized or specified that much at least in my part of the country.

-Mark

Does that cost include core drilling/retrofitting the door to accept wires? Or, is that not the issue that I am thinking it is? (Likewise with power transfer on the door, although the concern there is more vandalism than cost, or do hardwired concealed transfers really hold up better to abuse than a mortised-in wireless setup could?)

I’m not sure…and we may not be talking apples to apples. Mostly because what I’m referring to is new construction not retrofit and as far as the cost, I’m merely talking about the price of the actual components involved.

As far as power transfers…I typically will specify a separate power transfer…because I like each piece of hardware to do the job it’s designed to do…let the hinge be a hinge and the power transfer be a power transfer…this mentality typically makes for a more robust installation.

I hope this was helpful 🙂

-MK

Ah, you’re assuming the door comes from the factory with a raceway already present — how much (if anything) does the door factory upcharge for that option? (Looking at it from an outsider perspective, factory option-ing is a lot harder to get data on than “what does a distributor charge for a base door slab from stock?”)

And I agree that a separate transfer will always beat wires in a hinge or pivot, but at the same time, I do wonder about the different…vulnerability profiles between something like a wired concealed transfer and a wireless power transfer device…or is vandalism of devices like the Securitron CEPT not a concern in practice?

Yep…Since I work mainly on new projects with new doors, I’m always assuming the raceways are done at the factory…and I reached out to a distributor friend of mine and they tell me that the wood door companies only charge about $20 for a race way. As to your second question…I’ve never seen an EPT vandalized…I’m assuming that’s because it’s not exposed when the door is closed and secure.

-MK

Mark, as you with 41 years, I also into my 45th year of the industry. It’s still part of my DNA! That’s a great history lesson Mark! I had always assumed the electric strike may have been invented in the 1800’s by either Mr. Adams or Mr. Rite,,,,, Enjoy your posts, keep them coming!

Thanks Robert, and I was also surprised the the inventor’s name wasn’t more “familiar”.

-MK

hi, all valid points, but i am still not convinced. you missed the most important point, simplicity. an electric strike is a simple instrument to install, maintain and trouble shoot. if it fails, you remove it from the frame, 2 screws, unplug it and replace it. no power transfers, broken or frayed wires, power supplies, and alarm tie-ins.

Paul,

Yep, this is the reply I normally get from all maintenance staff. 🙂

-Mark

Check the total price difference between the 2 and you will have your answer as to why they recommend the more complicated system.

Tim,

Believe it or not even excluding labor (extra conduit runs) it’s cheaper to use an electronic lockset with RX and DPS built in than it is to supply all the individual items (E-STK, PIR & DPS).

-MK

Mark, thanks for your prompt response.

Tim,

Anytime 🙂

-MK

We often have to convince security system Consultants and Contractors. When it comes to access control, they only know an electric strike or an electromagnetic lock.

Hamza,

You hit on the exact reason I wrote the post! 🙂

-Mark

Indeed — the maglock brainworm is one of the worst things plaguing the access control world. (It even infects the designers of access control systems, who write documentation that basically presumes that you’ll be using a maglock!)

I had an experience once with electric strike techology during my Air Force service. I was stationed in Lewistown Montana in the 1960’s at a radar and ground to air communications site. I spent much of my time at the communications site about 3 miles distant over mountaintop roads. We ate noon meals at the radar site.

This site was a fortress of high security including door cameras and electrically released door strikes. One noon I impatiently rattled the door a few times and it came open! I reported my experience to the security office and they did not believe me. So I offered to demonstrate. A crowd hovered as I went outside and with a few shakes, entered. I understand that security added a new routine concerning doors with electric strikes – rattle the door.

Jerry,

Thanks for this first hand account and for helping me make my point…I may borrow your story 🙂

-MK

Thanks for the great article, I could not agree more about using electrified locks instead of strikes. I used to sell a lot of electric strikes at a wholesale house but after going in the field as a locksmith I realized the best strike is the one that came with the lock. Electric strikes as you point out are designed for multiple brands and often are not the best from an alignment perspective. They might work great when first installed but as time goes on the deadlatch might drop in or the door may bow a little or with frame shift and now it does not work properly.

Greg,

Thank You…I really appreciate the confirmation!

-MK